Want More Delectable Episodes? Subscribe to our Podcast!

If you’d like to receive the Foodal podcast episodes on your favorite devices, subscribe with your preferred method below:

Shownotes

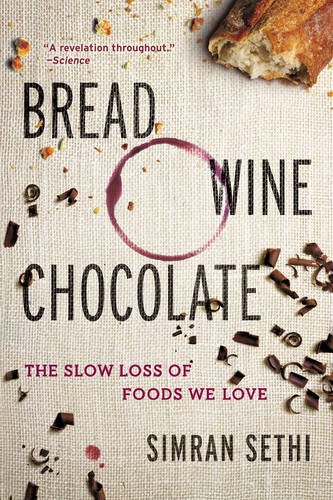

In the inaugural episode of the Foodal Podcast, managing editor Allison Sidhu interviews Simran Sethi, author of the book “Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods we Love.” Let’s listen in as they discuss:

- The origins of some of our favorite foods, like beer, coffee, bread, chocolate, and wine

- The importance of biodiversity

- The difference between foodies and eaters

- Experiential tastings, and the value of truly savoring our food

- What’s next for Simran (honey and cheese, anyone?)

Plus plenty of encouragement for the less adventurous eaters among us, and exciting news about the release of Simran’s book in paperback!

Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods we Love available on Amazon.

Transcript:

Allison: I’m Allison Sidhu, Managing Editor of Foodal, and today I’m speaking with Simran Sethi, author of “Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods We Love.” Thank you so much for talking with me today, Simran.

Simran: Thanks for having me.

Allison: I’m a big fan of your book, and I have so many questions that I’m looking forward to asking you today, so I was really excited to talk to you, and I want to just jump right in. So, first I want to ask if you could give me just a brief summary of your book for those who might be unfamiliar with it.

Simran: Absolutely! So the book, “Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods We Love” is a book about changes in food and agriculture told through bread, wine, coffee, chocolate, and beer. We couldn’t fit them all on the cover, but I wanted to tell the story that I think has not been addressed nearly enough, which is about the loss of agricultural biodiversity. And what that is, is essentially the loss of diversity in every component that makes agriculture and food possible.

So, the loss of diversity in soil, the loss of diversity in pollinators. You know, many of us are familiar with colony collapse disorder with bees, but all kinds of insects pollinate our foods. The loss of diversity in crops, in livestock, and straight up the food chain. At this time, 95% of our calories come from about 30 species, and three-fourths of our food comes from twelve plant and five animal species.

So, what we are effectively doing is increasing risk around food. You know, instead of diversifying like you would do, you know sort of like investment people tell us to do with any money that we might have, like “don’t put it all into one stock,” or something like that. Well, this is exactly what we are doing with food – we’re just growing high-yielding varieties in large order, disease-resistant varieties, but it’s really at the loss or at the expense of crops that are more diverse, more delicious, tied to our identity and places, and I think results in a loss of something that’s really not just about what grows in the ground but kind of like about what and who we are.

Allison: Right. Yeah, and I think that’s something that – to the degree that you touched on it in the book – it’s something that a lot of people might be sort of aware of, but not really to the full extent of it. I know, you know, the quote you just gave about 95% of the world’s calories coming from just 30 species. I know you also talked about agriculture as a series of decisions, and in the book you say, nearly every historic fruit and vegetable variety that was once found in the United States has disappeared.

To me, seeing it put that way, even though I have a food background – this is what I study and what I write about – to me, seeing it this way was a bit of a shock and it really felt like a call to action. And then I wondered at the same time if there might also be some people out there who see these sorts of statements as progress. You know, there are lots of fans of conventional food who like to eat at the fast food restaurants, that sort of thing. So I was wondering, why do you believe we should really be active and engaged and maybe even alarmed about this, and what can the average eater do?

Simran: That’s such a great question, and I loved how you built into that question because there is a component – you know, when I first started writing the book – I’ll tell you, I was in Italy doing research for a completely different project, and I had this book contract – this pre-existing book deal, and I started meeting with researchers and they said you know, “You’re worried about in your country about this, that, and the other, but what we’re really concerned with is the loss of agro-biodiversity.” And, like you, I’d heard of it kind of like a small way, but the scale of it I didn’t know. And I didn’t understand, and I didn’t honestly know why I should care either, because the grocery store looks abundant.

Friends would look at me puzzled when I would talk about the loss of diversity, they are like, “What? Have you been to a market? Have you been to a grocery store?” And it was only through the work – I spent five years on six continents really doing the research – that I started to understand why this matters.

The first reason, I think, is because it really is a risky way to grow food. It doesn’t make any sense right now. There was just a piece on Marketplace or – the Wall Street Journal ran it yesterday and the writer was interviewed last night on the radio talking about oranges in Florida, and the disease that has struck oranges is now resulting in a lot of citrus farmers just abandoning their crops. And that isn’t something that just happens to oranges – that’s exactly what’s happened to bananas. The banana that we grow now is basically an inferior replicate of the banana that was grown in the 1950s.

The challenge is, we can grow a thousand varieties of bananas, we can grow hundreds of varieties of citrus, but we grow one or two because they have such high yield, and because they may be resistant to disease. These are kind of the dominant two reasons that we grow food. But that’s not the reason we eat food. So I think when we look at this and pull out, as part of the bigger picture of how we eat today, of the choices that are available to us, that’s when it starts to become clear that we need more choice.

And for me I think – you know, you had mentioned fast food – that it’s a really interesting situation because what big agriculture will tell you is, “Well, we have to grow food this way,” but when we unpack that a little bit, what we learn is that right now we produce one and a half times enough calories to feed everyone on the planet; that’s everyone on the planet today, and the population of nine billion that we predict by 2050. That it’s not an issue of needing to create more food, it’s an issue of needing to create more access, to allow people to have the resources that enable them to buy food.

One of the biggest ironies for me was realizing that some of the hungriest people in the world are small farmers, and they are also the ones who are generating most of the crops that people eat. So, it might be like a small plot of land these smallholder farmers are growing food on, but when you take them in aggregate, they are the people feeding the world, and they are among the hungriest people.

So that doesn’t make any sense. When it comes to processed fast food, convenience is another reason we’ve lost diversity. People have this expectation that food should be ready in about five minutes. You know, pop it in the microwave or unwrap something and there is your breakfast, or lunch, or dinner. And then I think this is a real kind of erosion in identity and in deliciousness. I talk a lot about taste in the book as well, which is, the more comprehensive term would be flavor, but how we experience food. Again, companies have engineered their foods to really tweak out our taste buds. There was one nutritionist I talked to who was like, “They are trying to create this situation where everything is like crack.”

Allison: Yeah.

Simran: And your taste buds, you know, Doritos are like maximized now with all that orange dust on top of them, and you can see how people are really – you know, those flavors are so extreme, who wants to eat a carrot after we’ve had that kind of flavor overload? So I think this all ties together, and it’s really about better understanding of the sources of our food, and understanding what kind of came together – what forces worked together to get us to the place we are at now?

What we can certainly say is, a lot of the choice that we see is an illusion. It’s largely in flavor. There is tremendous brand consolidation throughout the food supply chain. So, you think you are seeing a bunch of different companies, and they are all owned by one company. Or you look at something like – I mention in the book, dairy products, I went to Walmart, which is the biggest grocery in the United States now. And 90% of the dairy products that you see on store shelves, be it ice cream, sour cream, milk, butter – all of it comes from one breed of cow, and it’s the Holstein Friesian which is the highest yielding dairy cow in the world.

So imagine what happens if that breed gets sick, or if the conditions under which it’s being raised right now change with climate change. These are the things that we don’t know, yet here we are. One banana in the store that’s now succumbing to a fungus called fusarium wilt. Ninety percent of dairy coming from one breed of cow. So you think there is abundance, but there really is this tremendous shrinkage that isn’t, again, just in these select crops, but across the board.

There was research done that shows that now the majority of the world is eating just a handful of foods, and – it’s wheat, rice, corn, soy bean, and palm oil – in increasing amounts and of the same varieties and types. So that kind of shows us that the trend is toward something that’s increasingly unhealthy, and just looking at our populations kind of bears that out.

Allison: Right. Right. So, I’m really excited to talk about taste. I’m going to get to that in a second because that’s a big focus of your book, like you said. But first, I want to go back to the idea of the small farmer, the different people who are manufacturing, growing, processing – every step along the way of getting our food to people’s tables. Why is it important to know where our food comes from, or more specifically, why is important to have an understanding of our food all along the food chain, and to learn about the producers and the processes involved that kind of get it to us?

Simran: You know Allison, I would say we don’t have to know. You can still wake up every day and have your cup of coffee or your tea or whatever – you can, I can – and we’ll have a fine life. But I think the reason that it grew in importance for me – like when I started writing the book, I thought I was just kind of writing about the foods and the farmers. And what I didn’t realize was that I was writing about myself. I was writing about how food informs my life and shapes my life; how coffee sets the tone of every single day of adult life; how chocolate has been my birthday cake, and my wedding cake, and my divorce cakes, and my book writing substance – that these things aren’t just calories. We celebrate with foods, we mourn with foods – that they are a thread of our lives and of our communities. And looking at it that way I realized, to understand them – you know, it is a total cliché, right? “To know me is to love me” – to understand them more was love and appreciate them more. And through that process, I was able to understand why diversity was so important.

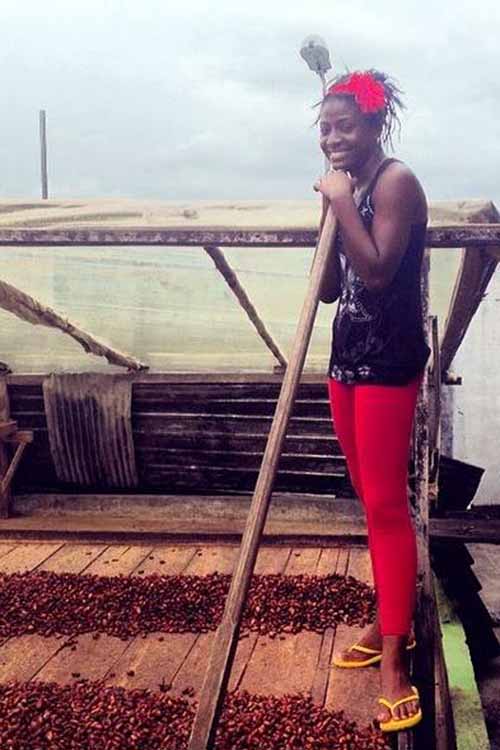

So, if just tell you like, “Hey! Guess what? Do you know where coffee was born, Allison?” Well, it’s Ethiopia. That’s the center of origin. That’s where coffee came into being. Well, that’s cool in and of itself. But then if I add to that, “That’s also the center of diversity. That’s where the most diverse varieties of coffee grow.” And then I add to that, “Well, we actually don’t grow very many diverse varieties of coffee. And now coffee is another crop that is succumbing to a disease, it’s called coffee leaf rust. It resulted in states of emergency throughout Latin America because it’s such an important crop for those farmers.” But it also puts our morning coffee in peril.

And there is all the variability, serendipity of climate change, like we don’t actually know what’s going to happen. Climate models show we could lose up to 100% of the diversity in coffee by the end of the century. So, then we start to consider, okay, well, that place far away is important because it holds this diversity that we might need. We might need to breed in some of the traits that are in those wild and diverse crops that are growing – the coffee crops in Ethiopia. But then I think what it also does, it brings home the fact that we start our days with an African crop, and wow, that region is undergoing severe drought right now. And no water, no coffee, right?

So all of a sudden, again, it ties us back to each other, and I think it makes the world a lot smaller, and it helps us to recognize our interdependence. So what happens is, this isn’t a coffee that I just pulled out of my cabinet, me, myself, and I. It’s something that ties me to the rest of the world, and to a bigger story. And I believe that’s why we should care, because if we don’t, then we are going to end up with highly mediocre coffee, and ultimately, possibly no coffee at all. And that’s just one example. I told the story through five crops, but as I say at the beginning of the book, map it onto anything you care about.

If beer is not your thing, do wine. If wine is not your thing, do juice. Because everything is being created within the same industrialized system – one that isn’t really looking at the long-term impacts, and instead saying, “We need to genetically engineer. We need to increase processing. We need to drive this to the bottom and make things cheaper, and cheaper, and cheaper,” when it’s like, “Well, first of all, that’s built on a false premise because we have enough food.” What we don’t have – just to repeat it because I care so much about it – is power. We don’t have access and we don’t have equity. So, it’s not that we don’t have food, it’s the people who are too poor to buy it, or for whatever reason don’t have access to it.

Allison: So, with these ideas of disease and diversity and the interconnectedness of everything in the food system, and also just because, like you said, you did go across six continents to write this book, can you describe just for a little bit about what you see as the future of food in the US, and maybe in the world?

Simran: It’s so interesting because when I first started, when the book first came out, someone posted somewhere, “This is a pretty elite way to go, isn’t it? Like you are asking everyone to eat all these fancy varieties of foods?” I kind of LOL’d back, and I was like, “Actually, um, this is how the world eats. America’s export is processed food. The Western diet is wiping out diversity that was rampant in the rest of the world.” So, I guess it’s an interesting thing to see it coming full circle, right?

So, America exported processed foods, and now the rest of the world is kind of going through that same experience, which is why you now find more people in the world, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization, are suffering from overweight and obesity, they’re are dying from these health-related diseases, than from being underweight. But we’re all kind of malnourished. We’re starved for micro-nutrients because the highly-processed diet is no healthier than a very diminished diet.

Some research that was done in Africa found that communities, even communities facing food insecurity that had close proximity to the forest and could forage for wild foods, wild plants and fruits and whatnot, had a healthier diet than those who had equal levels of food insecurity and lived in cities. So what I see, which I find really hopeful, is this kind of return to a place of respect for food, and increased curiosity. We’ve certainly heard about this, like, millennials love to know the story of their food. Okay! That’s awesome, because these stories are so important.

To me, of course, I love my iPhone, and I don’t want people treated poorly in factories. But I think what is equally as essential is to understand the stories of the farm, understand the stories of processing plants. And the fact that there are so many media outlets that are now dedicated to telling these stories is really heartening for me. And my hope is that the elevation and status of diverse foods, of a broader variety of foods – whether it be through farmers’ markets, through Slow Food’s Ark of Taste, through the conversations, and the kind of diversity of restaurants that are popping up all over the place – that we will see again a return to an increase in the creation of those foods in other countries.

Allison: Yeah. So, I’d like to bring this back around, like I said before, to taste. Why would you say that it’s important to enjoy the sensory experience of food, and why is it important to savor our food? I think this is something that a lot of people forget, and a lot of food is produced now for other reasons, in order to get the highest yields, not to make food that actually tastes good.

Simran: Exactly, and to just fulfill caloric nourishment. There is that food product called Soylent.

Allison: Yeah. Scary.

Simran: So when I was writing the book, I actually reached out – I can’t remember his name right this second – but, I reached out to the founder, and what I had thought about doing was ending the book with, “This is the future of food.” Like, I have taken you to the center of origin for all these other foods, now let me take you to the center of origin for Soylent, and it’s a factory.” He wouldn’t give me access to the factory, so that kind of withered away. But I think the reason that it’s important to savor food is because it is the most intimate commodity. It is our interface with the world around us. It is something that we put into our body that directly impacts our physical and mental health, and the way we interact with those around us.

So, for that experience to be stripped down to like, “We need these nutrients and this amount of calories,” I think flies in the face of an entire historical, archeological, culinary history that shows that food is one of the ways that communities come together, and food is the way that communities advanced. Right? That’s how we moved from being hunters and gatherers. That’s how our brains got bigger. We talk about like, “How did we get smarter?” It’s through the advent of fire, right? It’s through cooking things. It’s through preserving things. It’s through increased protein. It’s through all these things that enabled us to be the kinds of creatures that we are today.

So, for me, what has been frustrating in a lot of food books that I have read is, they say, “Okay. Dear reader, the planet is screwed. We are eating garbage, and the antidote is to cook things yourself, grow foods yourself, can things, pickle things, roast your own pig, bake your own bread, blah, blah, blah.” I feel like that’s really unfair. I think all kinds of change are really hard, and I think there is this audacious belief that just because we read it in a book, we’re all going to start like baking our own bread. I’m just not that person.

I’m someone who cares very deeply about food and our food system, and about justice in this system. I’m someone who cares deeply about delicious food. I don’t like farming. I used to grow some of my own vegetables, I didn’t really dig it. It wasn’t my thing. I cooked when I was married, I don’t really cook for one so much anymore. I really love the social aspect of going out with friends and eating or constructing very simple things for myself, but it was really like a situation where I didn’t want to be one of those people asking people to do something audacious in order to participate in the solution.

So, the solution is: eat differently. Be curious. Eat more deliciously. Okay! Well then, what are the tools for that? And that’s how I got to breaking down the senses in each chapter of the book. I married each of our senses – smell, taste, touch, sound, and sight – to a different food, and I talk about how the world kind of influences our perspective and why our senses work the way they do, and how they culminate in this experience of flavor, right? To really take in the deliciousness of the foods.

Okay, but then if I’m going to tell you to eat different versions of it, like drink the craft beer or eat the fancier chocolate, what tools do you have? Well, there are tasting guides in each chapter, again, for that very reason of wanting to empower people with as much information as possible and say to you, to me, to every eater out there, that you are your own best judge.

We don’t need Yelp reviews. We don’t need Michelin stars. We don’t need the editors of “Eater” to tell us, you know, or any website or food magazine or whatever, to tell us what’s good for us because everything is so deeply personal. I think, if we understand how our senses work, how our food is made, that through that evolution and that understanding we will start to make different kinds of decisions that will not only favor, I think, a healthier food system, but one that’s more delicious and anecdotally more nutritious as well.

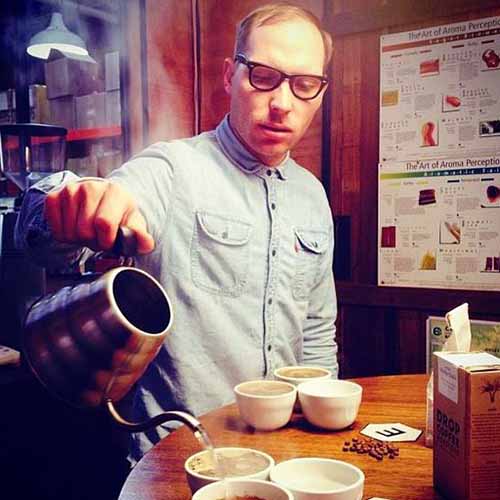

Allison: Right. I really love this experiential part of the book. I mean, you tell so many great stories, but I think having these sections kind of takes it to the next level and gives readers a project that they can engage in. And maybe some people, like myself (I studied Gastronomy at BU and tastings were a part of the curriculum there, for anybody who hadn’t maybe experienced them in working in fine dining or something like that before). But for some people who might pick up your book, maybe they’ve never really thought about the beer that they’re drinking in the sense of, “This tastes like this.” Maybe they’ve never seen – I don’t know how you make it this far if you are interested in food, but just to imagine it – maybe you’ve never seen a tasting wheel. And I know that you talk about meeting with Ann Noble, the sensory chemist who developed the wine aroma wheel, and she says it was created to democratize the experience of drinking wine.

So I want to ask you a little more about – you just said it’s about your own personal interpretation and what you get out of it, and we know that everyone’s tastes are different and experience of taste is different as well, but I wonder what you really think of the idea of being able to express what we taste. You say “language allows tasting to become more of a united experience and helps provide a level of consistency in how we evaluate what we eat and drink.” How does this kind of play into the idea of savoring our food and getting this real lived experience out of what we’re doing, rather than just the eating for calories and for nutrition?

Simran: I think it helps us to get closer to what we want by being able to have a language for what that is. So, for example, I was so intimidated— I’ll back up and say when I met Ann Noble, she created this wine aroma wheel, one of the foundational wheels upon which a lot of other wheels are built, and I went into her kitchen.

First of all, she like completely forgot about our appointment. So she was like, “Who are you?” I was like, “Wait a minute! I mean like I’ve been sweating this for days, like what?” And we’re sitting at the table with a bunch of other wine people, sensory analysts and what have you, who were also there for lunch. And then she talks about the merits of blending wines from Trader Joe’s – you know, and how Two Buck Chuck, something about how great it can be when blended with something else. And I just, it blew my mind. Because here we are in Davis, California, beautiful home. She takes me out to her garden, gorgeous. Very idyllic. We’re eating beautiful cheese. She offers wine. I pretend to be virtuous and say no but, I mean, I was being virtuous but unnecessarily so. But the thing was, she was just real, and she was normal, and she made me instantly comfortable about the decisions I was making. And I have in my life, even after doing all this work – maybe some of people who will read and listen to this as well will know like that experience of being in a tasting of some sort, and you kind of look to the sommelier for approval, for tacit approval of whatever it is you think you’ve found in the wine, or wherever you are like, “Yeah. This is good.”

I really think so much of this experience has been put on someone else to decide, and I don’t want people to feel that way. I feel like we have such complicated relationships with food – I certainly do. But I want the tasting experience to be one that is joyful, and to be one that I feel I can own completely.

I think I would argue a lot of people who do lead tastings don’t know how all the senses function. I’ve been to plenty of tastings where all people are doing is very quickly talking people through something, and saying like, “Oh! Cherry bark. Wood. Nutmeg,” and then they move on. And it’s like, well, maybe that person never tasted any of those things. And maybe if you explain to them your point of references are cultural as well as circumstantial, then maybe it would be different.

And when it comes to this language – you referenced my quote earlier – what language does is, it helps us communicate to each other. So if I say to you, “Allison, this tastes sweet to me,” and my points of reference for “sweet” are honey-based, let’s say, as opposed to sugar-based. You know, if you think of someone having like a baklava over cake, those are both sweet things, but the sweetness comes from two different places. Those are the kinds of things that shape how we show up at the table.

So for me, it provides a lot of delight. And the only utility, honestly, in doing this isn’t to be like one of those poseur people like sticking their nose in a beverage and pulling out all these flavor notes and sounding very fancy. It’s only to have the language to say, “Huh! What I liked in that beer were the caramel notes, or the buttery notes, and I know that comes from diacetyl. And I know that that can be considered, like what are the other beers that will offer this kind of taste to me? Oh! It’s the sour beers,” or what have you.

So, you’re able to take a journey where you are able to again find what you love. And that, to me, is the utility of this. It’s being able to sit around, take those wheels in the back. You know those of us who are the rookies often feel intimidated, but one of the big things that separates the professional tasters from the rest of us is, they have a language. They have a language for describing what it is that they are tasting. Where I might just say, “This coffee tastes like coffee. Oh, I think it tastes a little bit sweeter than the other one,” they’ll say, “Where does that sweetness come from? Is it a fruit-based sweetness?” Like, where is it?

So being able to dig – so the wheels have words on them that are descriptors – and it’s also being able to pull from experiences. That’s another big point of distinction. So, to be able to say, “Oh! This tastes like something I had before. What was that thing?” and paying attention to it, that sensory recall. So, I think the book was designed to be very user-friendly. To be something that, hopefully, people would pull off the shelf, open up a bottle of wine, and go through with their friends.

And then again, like I say in the book, I’ve just given you five foods and drinks, but now you can do it with everything. Maybe there’s not a kale tasting wheel, you know? But there certainly is one for honey, or cheese, or whatever. But that now you’re empowered to explore food on your own, and pull out what you love on your own, so you can find it again in your own way.

Allison: Yeah, and it’s accessible to anyone, like you said, so I thought that was great.

So, another thing that you talk about, unlike your… I guess virtuous refusal of that glass of wine… there was another glass of wine that you said yes to, and it was kind of a magical glass of wine that you say transformed you. And in the book you also say at one point, I think near the beginning, you say “Taste is a reflection of who we are, and what we’ve been exposed to, and what’s expected of us in a given group or society.” But you also say, “Every new bite, every new sip can change us if we are present and open to it.” So that kind of leads me to the question, what advice do you have for the eater who always orders the cheapest option on the wine list, or the fast food addict, or the picky eater – the person who doesn’t really feel inclined to explore?

Simran: So, first say, “Welcome, comrades,” because I am one of you, actually. This adventurous eating version of me is pretty new. One of those turning points for me was that glass of wine. It showed up, I had just interviewed one of the people who is in the book, a chocolate maker in San Francisco, and I said, “Yeah, just surprise me.” I was just having this rare moment of openness. and this woman, Ali [Hamerstadt] is her name, shows up with this glass of orange wine. I had never seen anything that color – it looked like a sunset. I had never tasted anything that was sweet and also so – hint of effervescence, really mineral – these things all came to me in this glass and I all of a sudden realized there was so much that I had been missing.

And then I managed to discover this in coffee. It didn’t come right away. These aren’t things that necessarily bump people over the head, but I think, to experience, them is to experience food in a whole new way, which is, by extension, to experience life in a whole new way.

I don’t like a lot of unpredictability. I don’t consider myself adventurous. I’m the person who looks at stuff online and figures out what I’m having for dinner before I even go to the restaurant. I order at the same thing, I know what I like, and I don’t like to be disappointed. So I order the same thing over and over again.

But I’ll tell you, my life has gotten so much more interesting this way. It is such a low– well, this is going to sound a little bit confusing – but it’s a low-risk way to take risks. Sure, I could try a new origin for my cup of coffee, and then maybe that will build my capacity for trying a new experience, like trying a different sport, or taking a dance class, or an art class, or what have you. But that these things build on each other. One of the most interesting pieces of research I came across was like, how do people get over their reluctance to eat new foods or their fear of different foods? And the answer is repeated exposure.

Allison: Yeah.

Simran: So, it’s trying new foods, is the way to get over being scared of new foods.

Allison: Right.

Simran: And having information about it. So the two primary ways are to have a lot of information about it and to taste it. And if you think about how a child gets exposed to new foods and how we all kind of grow up and move through the world, it is much safer to stick with what we know. When we’re on limited budgets, even more so. But I do think injecting even a little bit of adventure in there and a little bit of risk-taking is to, sure, open ourselves up to the chance of disappointment, no doubt. But what I’ve also found is, it’s to open ourselves up to the possibility of joy and satisfaction, and a savoring that we didn’t know existed, and that was my journey. That’s what the five years did to me.

On the other side of that, I’ve realized how much food means to me. And how – trust me, I’m a writer – I don’t make a lot of money at all. I love this thing called food, and I love it in ways that aren’t just academic. I cherish a good meal, and I see the connections, and I see what it does to me, and this is how I want to live.

Allison: Yeah. So, at the end of this big adventure that you went on in the project of writing this book – and maybe it was that glass of wine, you’ll have to tell me – but what was the best thing that you ate while you were writing the book, and what made it so memorable?

Simran: Ooh. Two things… Well, gosh – see, now I want to say like seven.

Allison: Yeah.

Simran: Okay. First, it was the wine. So, I will say because it was such a surprise, this glass of Jolie Laide Trousseau Gris. It’s a grape that is grown on one ten-acre plot in North America, and that is in the Russian River Valley by a guy named Peter Fanucchi. Peter is politically very conservative, and I’m politically very liberal. So we’re the complete opposites. And then here’s this guy conserving the grapes that make the wine I love, and he is the only one doing it commercially, right? You could grow this grape Trousseau Gris all over Northern California, but it’s not grown. It’s not one of the seven dominant varieties of grapes that are grown, right?

So, he’s already doing something precious there, and because I wasn’t expecting it, I think that really knocked me out. The story knocked me out. At the time, I just thought I was having a glass of wine, and I was writing a book about, honestly, corn, potatoes, rice. I was going to sprinkle maybe some chocolate on top, maybe a little wine. It was going to be like a two-page sidebar thing – it wasn’t the book. And it helped me to realize how much I could love something as simple as a glass of wine.

And then it was coffee. I was trying so hard. I was living in Australia, but I got invited to be a visiting a professor at the University of Melbourne in Australia. And I’m living in Melbourne, and I walk into this coffee place, and I was like, “I’m writing a book on food, guys,” like, you know? [Laughs.] I can’t find any of these flavors in my coffee – any of these smells, these aromas, these tastes – all I taste is coffee, and I’m getting hyper-caffeinated even though I we’re spitting it out [Allison laughs], but I go to tasting after tasting after tasting, and I would just leave wired and angry. And they were so compassionate and it helped me to realize like this doesn’t – maybe for some people it like falls on them like a waterfall, but for me it took a minute. And it was when I was quiet by myself with a coffee a friend had sent me. Interestingly enough, it was an Ethiopian coffee by way of San Francisco.

So it had been roasted, it was just like a home care package. And I tasted like flowers in my coffee. And I was like, “What is this? This is crazy! Where did this come from?” And it started to open up the world for me.

I had the grace and the blessing, the good luck and the whatever to have left my job – I quit my job, I sold my house, I went on this adventure – and to have gone to these places in the world. But you can visit Ethiopia every morning in your cup of coffee, right? You can taste the origin of Ecuador in your chocolate bar. You could savor the hops, the royal hops from Europe, in your beer.

It’s just extraordinary how the world shows up on our plate, and I think that’s also been a really key part of this for me – you live in an era where we can find out so much about each other from great distances. And one of the most intimate ways to understand those relationships is through food. So for me, it’s a really exciting time. We have a local food movement that is thriving, but we also have a global orientation that reveals our connection to other people in other places.

Allison: Great. So you refer to yourself as an eater. What do you see as the difference between a foodie and an eater, and what’s the importance of this distinction? What would you say is the job of the eater?

Simran: So I think the “foodie” is a great way to distinguish ourselves as being something fancier, right? “Oh, I’m not an eater – I’m a foodie.” And that maybe has its place, and for certain people it’s a badge of honor. But for me, that’s not where I want to be, and that’s not how I want to consider or approach food. I find deliciousness, you know I mention in the book, in like a bucket of yucca in Havana and like the diner in India. It’s about being present and it’s about savoring.

It’s not about going to the fancy restaurant. And to me that distinction is really important because that just is a way to split people away from each other. And once this becomes a foodie movement, then it means it doesn’t belong to everybody else. But if the foodies were going to solve this problem, we would have done it by now because, how much more Chez Panisse can we get? God bless Alice Waters and all farm to table restaurants, but we need a movement that includes all people.

We need a movement that brings people to the table and gives them a seat, and that, to me, is what being an eater is all about. It’s about saying your food traditions are different than mine, your diet is different than mine, your orientation is different than mine, but this is something we actually share. And the minute we can find points of commonality around that, we have a chance of solving these problems together.

And by “these problems,” I mean everything from the challenges around climate change, to income disparity, to challenges we have with our diet, to trade agreements – all of this falls into that bucket because food and agriculture touch and are touched by all of these issues. Even “eater” has its own set of connotations, but I don’t really know what to say other than like, “We are all in this together.” As Wendell Berry says, “Eating is an agricultural act.” So it’s to recognize that this is something that we participate in, and this is something that shapes the world every time we do.

Allison: There is a lot to think about there as far as all the different components that come together in farming and our access to food, and the politics, and climate, and environmental aspects of it that are all involved, and it’s hard to focus on just any one aspect of that if you’re really on a mission to create change.

Simran: But it is also – imagine like the minute we eat more diversely and lower on the food chain, we’re looking at addressing issues of the environmental impact of food and of climate change, right? Just as an example.

Allison: Sure.

Simran: So it’s like, the minute I go to the farmers’ market and choose to get my greens from Moon on the Meadow instead of the box of organic greens shipped in from wherever, I’ve already made a decision to support my local economy. They are organic. They’re not certified organic but it’s a relationship I trust with my farmer, and it’s really healthy, delicious, seasonal eating.

So that’s what I love about food. It’s so… like I don’t have this relationship with the grid. Energy is really important. I don’t have a car, but I’m borrowing one right now. The car is really lovely. The lights are necessary, but, like, do they make me excited? Do I think about turning on the lights at any given moment in time? No. But am I already thinking about what I’m having for dinner at 12:46 p.m.? Yes. Absolutely! I know what I’m going to have for dinner tonight, and I’m excited about it!

And so, I guess that’s another thing. This food has the possibility of celebration which, maybe if you were living in a place that doesn’t have any electricity, maybe one has that same experience then. But I have the luxury of saying like, “I don’t give a lot of thought to my lights going on and off.” So it’s become muted, and it’s also like it feels very abstract, like the electricity just comes. I have a fairly sophisticated understanding of the grid, but still, it’s nebulous to me.

So, yeah. I just think, we eat this a couple of times a day. We eat this decision, and we eat this transformation. And I guess I just want us to use that power wisely, in ways that serve us, in whatever ways that those are. I recognize they are individual and contingent upon geography and class and a whole host of structures, but I also think we all have agency. We all have power within and to arm people with as much knowledge as possible is to, I think, increase the opportunity of choices that will ultimately support all of us.

Allison: Yeah. So, after all these experiences that you got to have, and the research that you gathered, and all the foods you tried, what’s one thing that didn’t make it into the book, or maybe that you’ve discovered or learned or tasted since the book came out and would love to tell your readers about?

Simran: You know, I will say I’m pretty excited about cheese – cheese as a carrier of such deliciousness and so many stories. I had the good fortune of attending the American Cheese Society’s annual conference in Iowa and it is such a democratized industry. Like, it’s not just fancy food people, you know? It’s dairy farmers right alongside.

So, if you look at something like coffee or chocolate, both coffee and chocolate are produced in countries that are in a belt around the equator. But then they are roasted, possibly, in other places, right? You get coffee roasted in Kansas City, or in Amsterdam, or what have you. So that distance is quite long.

When it comes to wine, when it comes to cheese, the terroir is, it’s like a tight kind of expression of the taste of place. Because the cheese makers are right there beside the dairy farmers, or may, in many instances, be one and the same. And the wine makers and the grape growers are also in close proximity. So, to me, I certainly considered that with wine, but I didn’t actually know that also existed in cheese. And fat is such a glorious substance because it holds all of the aromas – the smells that make up most of our experience of flavor.

So, that’s why I love chocolate so much. Chocolate comes from cacao, which is a seed that’s about 50 percent fat. So, it’s got a lot of flavor compounds in there. Well, of course cheese is the same way. And so I guess I would love to do an exploration of cheese and honey. If given the chance, those might be my next two.

Allison: That sounds great to me. I would love to read it. I mean, I wanted to ask you what’s coming next. Maybe a book about cheese and honey could be it! I want to ask you too about the release of your book in paperback, which we’re really excited for.

Simran: Thank you. So, cheese and honey, yes – I would love to do that. I have to say, what has been my dream – two dreams, kind of in tension with one another – one wins out every other day – is a book on yeast, because I’m just absolutely fascinated by that microbe. Yeast is something I learned about a lot through my beer chapter. So, yeast is what turns the juice to wine. It’s what makes beer alcoholic. When beer is in its earlier form it’s called wort, which is barley water or grain water. One could say sweetened grain water. So, it makes beer, beer. It makes the bread rise.

So these are all cool functions of yeast in food. It gives chocolate its flavor through fermentation. But what it also is, is a very simple cell structure. It reproduces rapidly, but it has a nucleus. So, we often use yeast to test pharmaceuticals. We use yeast to understand basic life processes. So, for me, it’s like understanding yeast as like a reflection of who we are. It’s kind of this crazy thing, and with all of the microbiome stuff we hear about, a lot of that talk is around bacteria. So, yeast is getting short shrift.

So, I’d love to write a book on yeast, but I would also equally love to write a book on chocolate because I feel like a lot of the information that’s out there is great, but is kind of just giving the surface of the bigger story. Chocolate is one of those substances that can be the lens for everything: for history, geography, politics, slavery, chemistry, biology – the list goes on and on. So I would love to try to tell that story as well.

Allison: Yeah. Again, that sounds great. I’ll be first in line to read it.

Simran: Awesome. I have an audience ready to go.

Allison: Yeah!

Simran: Thank you.

Allison: And like I said, the audience for your paperback is here too. You told me it’s coming out on October 18th?

Simran: Yes. It is coming out on October 18th. I’m very excited about this. This is a book that means a lot to me, and I wanted to make sure that the paperback retained all of those great wheels and everything. So you’ll see it’s just a really easier-to-carry version of what’s already out there, also beautiful. Some really great support for the book came in as the hardcover was released, so you’ll see a lot of that kind feedback in the paperback as well. And I’ll be doing a little bit of touring around the paperback, which people can find out more about through my website.

Allison: Great, and how do they get to your website? What’s the address?

Simran: It is www.simransethi.com, and if you click on the book on the homepage, it’ll take you to all the info about where I’ll be.

Allison: Excellent, and yeah, the portable paperback sounds great to me. I wish I’d had that option. I spent a lot of time reading my copy on the airplane and in the bathtub [Simran laughing], so paperback could have helped me out a little there! But it’s alright.

Simran: The good news is, the cover already looks a little bit messy, [Allison laughing] so [if you get something on it], no one knows.

Allison: Yeah. Yeah. Eating while I’m reading it, yeah, definitely. So, final question: what do you hope that your readers will take away from the experience of reading “Bread, Wine, Chocolate”?

Simran: I hope that readers will take away a real sense of how we’re connected to each other, and how much we rely on people in places that we may never see for the things that we love. And I think through that, I hope we feel a greater sense of gratitude for what comes across our plates, our tables. And I hope that the tools I’ve offered will open people up to curiosity, right? I can’t make you put that food in your mouth, but what I hopefully have done is created the conditions where you’ll want to try a different beer, or you’ll want to taste a new chocolate. That the tasting guides and the information on the sensory experience of foods will help support a little bit more adventure in people’s lives.

Allison: Yeah. I think it definitely was an adventure reading it, and you can take it to the next level and, like you said, enjoy trying these new foods with your friends and really experiencing taste. I’m really excited for anyone who’s reading on Foodal who hasn’t read it yet, to really run out and get it, and then pass it along to someone else because it’s a wonderful read.

Simran: I also just want to mention, if you see that I’m doing an event anywhere near you, you should also know that I’m probably doing a tasting along with it. That’s really been important to me. So, added incentive.

Allison: Exciting! That sounds like fun.

Thank you so much for talking to me today, Simran.

Simran: Thank you.

Savoring Our Food, One Delicious Dish or Cup at a Time

Did you like what you heard? Please subscribe on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts, and give us a five-star review. We’ll be back in about a month with the next episode!

What would you like the Foodal Podcast to explore? We want to hear from you!

Photos by Simran Sethi and Jana Dambrogio.

About Allison Sidhu

Allison M. Sidhu is a culinary enthusiast from southeastern Pennsylvania who has returned to Philly after a seven-year sojourn to sunny LA. She loves exploring the local restaurant and bar scene with her best buds. She holds a BA in English literature from Swarthmore College and an MA in gastronomy from Boston University. When she’s not in the kitchen whipping up something tasty (or listening to the latest food podcasts while she does the dishes!) you’ll probably find Allison tapping away at her keyboard, chilling in the garden, curled up with a good book (or ready to dominate with controller in hand in front of the latest video game) on the couch, or devouring a dollar dog and crab fries at the Phillies game.

Yay!!! I’m glad you guys have a podcast, I’ve always thought the site needed one. Thanks for the new addition and can’t wait to hear more shows.

Thanks so much, Shelly! Don’t forget to like, share, and subscribe!