When I asked my dad if he grew up eating chestnuts, he immediately lit up, as if reliving old memories that he thought were long forgotten.

My grandfather Poppy, my dad’s father, rarely made a meal for the family to enjoy at dinnertime. He would work, and my grandmother would cook every day for their five children.

He quietly relied upon my muumuu-and-apron-clad Mimi, who would excitedly shake a spoon dripping with red sauce while loudly talking to the family.

But when winter approached, Poppy was exclusively responsible for one dish:

Roasted chestnuts.

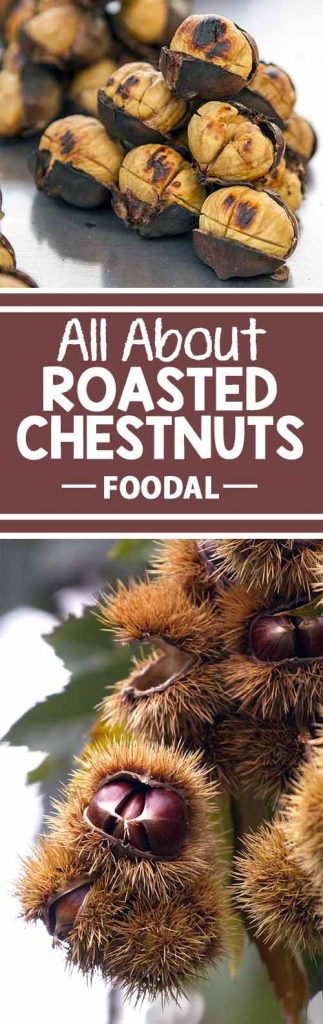

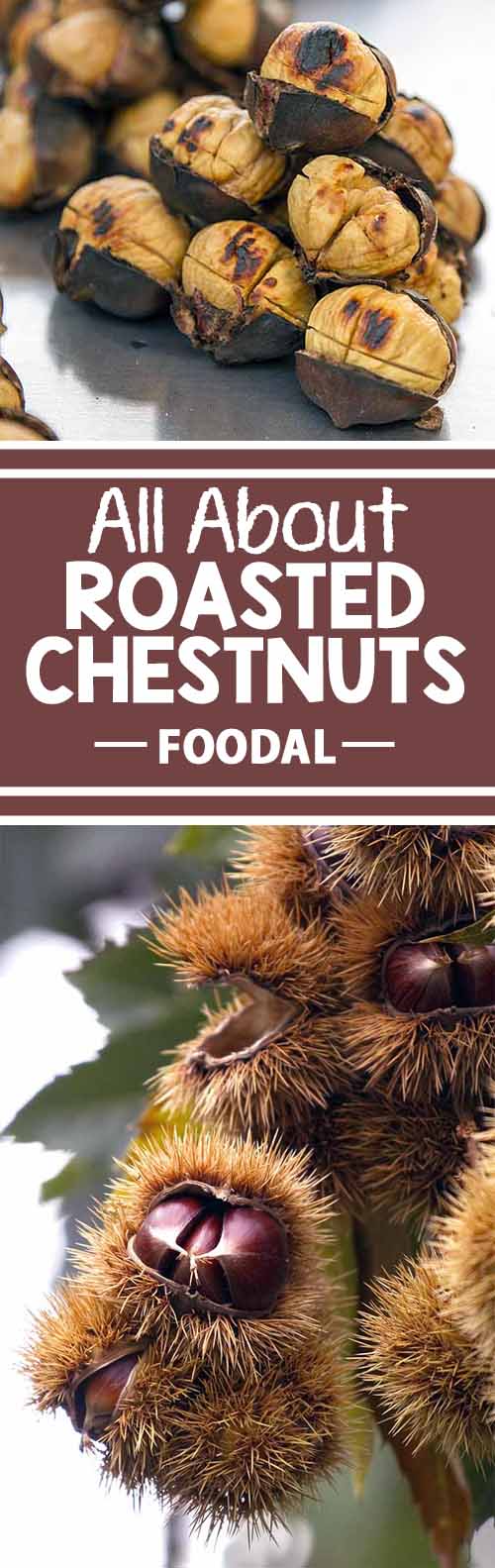

One weekend each chilly winter, Poppy would walk around the 9th Street Italian market in South Philly and buy a bag or two of chestnuts to take home. He would score the shells and roast them over the wood fire in the living room fireplace.

Once they were perfectly toasted, and the sweet, earthy aroma filled the house, Poppy would serve them accompanied by food found in any typical Italian-American home: figs, apples, and glasses of Chianti.

For my father, while he didn’t particularly like the taste of them (but would never say no to a sip of wine), he still enjoyed the special experience every winter. As a young child right through to his years spent as a college student visiting home for winter break, my dad loved the sounds of the crackling fire, the fragrance of toasted nuts, and spending time with his family.

Even though my dad never roasted them himself, and never taught me or my brothers how to roast them, the winter holiday season has inspired me to learn more about this sweet annual pleasure.

I am happy to share with you what I have discovered about these toasty nuts, and how they have been known and enjoyed as a seasonal delight for thousands of years throughout the world.

The Nutty Necessities

The chestnut tree is a fast-growing deciduous plant, representing one of the most important nut crops in the temperate zone.

Chestnut trees belong to the genus Castanea. Under this genus category, there are four leading species of chestnuts that have long been cultivated for thousands of years, indigenous to all three continents of the Northern Hemisphere.

Using information provided by Paul Vossen, the lead farm advisor for the University of Californa’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, let’s take a quick look below at the four most common pure species that make up the majority of commercial production:

Castanea Sativa

C. sativa is the European chestnut, native to western Asia, Europe, and North Africa. Chestnuts from this species, particularly those produced in Italy, make up most of the nuts imported to the Unites States.

Castanea Crenata

C. crenata is the Japanese chestnut, native to China and Japan, and it is found in hilly and mountainous regions. The nuts are large with a coarse texture, and they lack the sweet flavor that the other species possess.

Castanea Mollissima

C. mollissima is the Chinese chestnut, native to China. It ranges from south China to the north of Beijing, and western China as well. With its fine texture, it is currently the major commercial species of this nut.

Castanea Dentata

C. dentata is the American chestnut, native to the eastern United States and parts of Canada. It grows mainly in the Appalachian forests from Maine to Georgia, stretching as far west as Michigan and Louisiana. The nuts from this tree are much sweeter than most other species.

This species was nearly wiped out due to a chestnut blight in the early twentieth century, when Asian chestnuts imported to America inadvertently spread a fungus that devastated the crop. Even though the Asian varieties were resistant to it, those that were native to America were nearly all destroyed.

Since then, there have been extensive efforts to revive the American chestnut. It is making a slow comeback thanks to the aid of organizations like the American Chestnut Foundation, and the development of small, thriving hybrid reserves throughout the United States.

With its different species ranging across the world, chestnuts have a global presence that dates back thousands of years. And they still continue to be a stronghold in commercial nut production today.

Keep reading to learn more about their history and prevalence in Asia, Europe, and America.

China and Japan

This nut has been eaten in China since antiquity, dating back to the fourth or fifth millennium B.C. Writer Frederick J. Simoons notes in his book Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry (available on Amazon) how the “acceptability of the chestnut is indicated by the fact that its nuts were suitable presents for the emperor and were sent as a tribute.”

And what’s deemed acceptable for the emperor is certainly suitable for the general public! Roasted chestnuts were a common street food in China and Japan during fall and early winter, where they were sold outdoors in many towns and at street intersections.

Fast forward to the present day, and China has become the leading producer and exporter of chestnuts with an annual production of 110,000 to 265,000 tons.

About a third of this annual harvest is exported to Japan, which is one of the largest chestnut-consuming countries in the world, and the biggest importer.

The Mediterranean

As for European history, the nuts were cultivated at least 3,000 years ago in the mountainous regions of the Mediterranean.

Many European communities of years past, both the rich elite and poor peasants, relied upon the resourceful qualities of the chestnut tree.

In Tuscany, it is often referred to as l’albero del pane, “the bread tree.” This was because the nut offered an ingredient that provided many culinary uses.

It was the staple starch used in many homes: boiled and mashed like a vegetable, used in stuffing, stews, soups, purees, roasted whole, or dried and ground into flour and eaten as a bread or a porridge.

The United States

Ever since the first European settlers found native forests of American chestnuts a few centuries ago, the United States has been a major contributor to the chestnut’s popularity.

During American colonization, the tree not only provided delicious sustenance for both humans and animals, it was also used for a variety of non-edible purposes. The wood provided a strong material for railroad ties, house framing, barns, and fences, fuel, and even tannin for leather processing.

Even after the chestnut blight of the early twentieth century, it still continued to be an essential food item in the United States during the winter months.

While the US represents less than 1% of total world production, it does a great deal of chestnut imports. We’re talking $20-$40 million worth of the product annually, mostly brought in from Italy and China.

Especially during the winter holidays, American markets have a high demand for these nuts. According to a timesunion article written in 2011, a grocery store chain in Connecticut sells over 20,000 pounds of chestnuts annually between November and January.

Why Only Winter?

Chestnuts are a very seasonal product, typically available fresh for just a few months out of the year in the fall and winter.

Naturally, they are a winter staple.

Lane Morgan puts it simply enough in her Winter Harvest Cookbook, available on Amazon: “Everything is best in its season.” Chestnuts are no exception. Morgan explains that they reach their peak of flavor in cool weather.

Winter Harvest Cookbook: How to Select and Prepare Fresh Seasonal Produce All Winter Long

While they can be preserved for long-term storage to be consumed throughout the year, using methods like flour milling and pickling, they should be consumed soon after the late fall harvest for the best fresh experience.

And Why Roasting?

Whether they are cooked in a fireplace indoors or on a pushcart at a street corner, one of the main reasons why chestnuts are roasted is that it yields their best flavor qualities.

Sometimes chestnuts can be too bitter when consumed raw. Contributing writer Johanna Uy of The World’s Best Street Food: Where to Find It and How to Make It (available on Amazon) can attest to this, after researching the European tradition of street vendors roasting nuts. She observed that the “unpleasantness of raw chestnuts is miraculously transformed, with their sweet taste and fuller flavor emerging only after a good roasting.”

Roasting also helps to slightly loosen and soften the rock-hard casings, making it easier to peel by hand. Peeling them while still warm is “all part of the ritual” that you need to endure, Uy writes. After peeling and prying for a few moments, you are soon rewarded with a delicate and nutty taste and a rich, silky texture.

Aside from its delicious flavor, roasting them on an open fire is also a lucrative tactic employed by street vendors across the globe.

Heat sources like open fires and grills not only serve as a practical means of warmth and shelter during the cold winter months, but they also are the perfect man-made tools for all sorts of outdoor cookery, including roasting fresh chestnuts.

Especially during chilly outdoor winter festivals, many street vendors would sell bags of them, or have them neatly arranged in rows to display the beautifully busted shells and the lightly charred flesh – patrons would keep warm by the hot charcoal or wood fires and potential customers would easily be seduced by the sweet aromas of roasted nuts.

Quite the easy marketing campaign – and it still works today!

The Ubiquitous “Bread Tree” Now Embraces Holiday Limits

Approaching modern times, the chestnut has largely lost its multi-use value as “the bread tree.” It most regions today, it is mainly known as a winter holiday staple, particularly in New England and abroad in Europe and Asia.

It’s a sad truth that many in America have never even tasted or even seen chestnuts.

For the most part, the chestnut is no longer a cornerstone of the kitchen, no longer needed to make basic flour or other starch-based dishes that are often dominated today by wheat products or the use of others grains, thanks to improved farming techniques, industrialized processing of foods, and other modern-day factors.

Because of this, chestnuts are usually reserved for holiday dishes today, like Thanksgiving stuffing, or enjoyed as an indulgent street food. And these traditions amplify its use as more of a winter specialty item than an everyday kitchen ingredient.

Revisiting a Holiday Memory

It’s been years since my father smelled the sweet, nutty fragrance of chestnuts roasting on an open fire, like he used to enjoy at his childhood home so long ago.

Many believe that chestnuts are now just a small piece of Christmas nostalgia, present only in the sweet melodies of carols, the occasional toasty cup of hot chocolate, and perhaps as an ingredient in someone else’s stuffing. But the sweet pleasure of a rolled up piece of parchment paper filled with warm, toasty nuts is still enjoyed each winter throughout the world.

And it didn’t take much convincing for my father to start researching where he can buy chestnuts to toast this winter… just like Poppy.

Do you have any memories of roasting chestnuts on an open fire? Or are you hoping to create new memories by trying them for the first time this holiday season? Let us know in the comments below!

Photo credit: Shutterstock and New Society Publishers. Significantly revised and expanded from a piece originally written by Allison Sidhu.

About Nikki Cervone

Nikki Cervone is an ACS Certified Cheese Professional and cheesemonger living in Pittsburgh. Nikki holds an AAS in baking/pastry from Westmoreland County Community College, a BA in Communications from Duquesne University, and an MLA in Gastronomy from Boston University. When she's not nibbling on her favorite cheeses or testing a batch of cupcakes, Nikki enjoys a healthy dose of yoga, wine, hiking, singing in the shower, and chocolate. Lots of chocolate.

The first image in this article is of a horse chestnut which is toxic if consumed.

You are absolutely right, Sam. Thank you for catching this mistake! The article has been updated.