We occasionally link to goods offered by vendors to help the reader find relevant products. Some of these may be affiliate based, meaning we earn small commissions (at no additional cost to you) if items are purchased. Here is more about what we do.

I’m a foodie, and a bookworm. I found Mark Kurlansky’s book “Salt: A World History” and Gary Taubes’s “The Case Against Sugar” to be on-the-edge-of-my-seat compelling, and I was hungry for more.

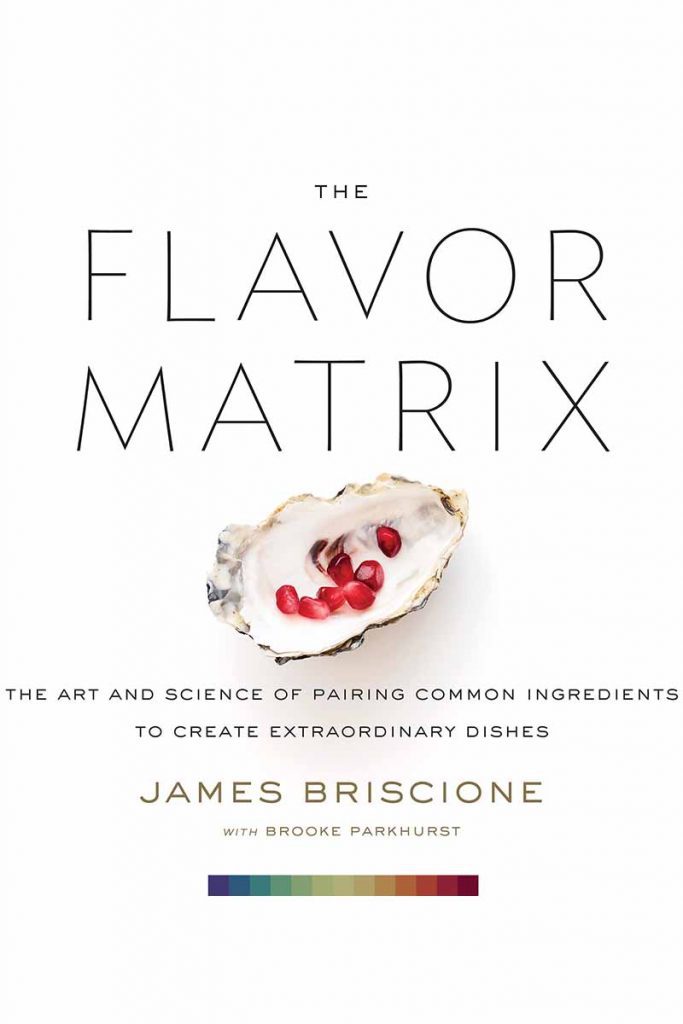

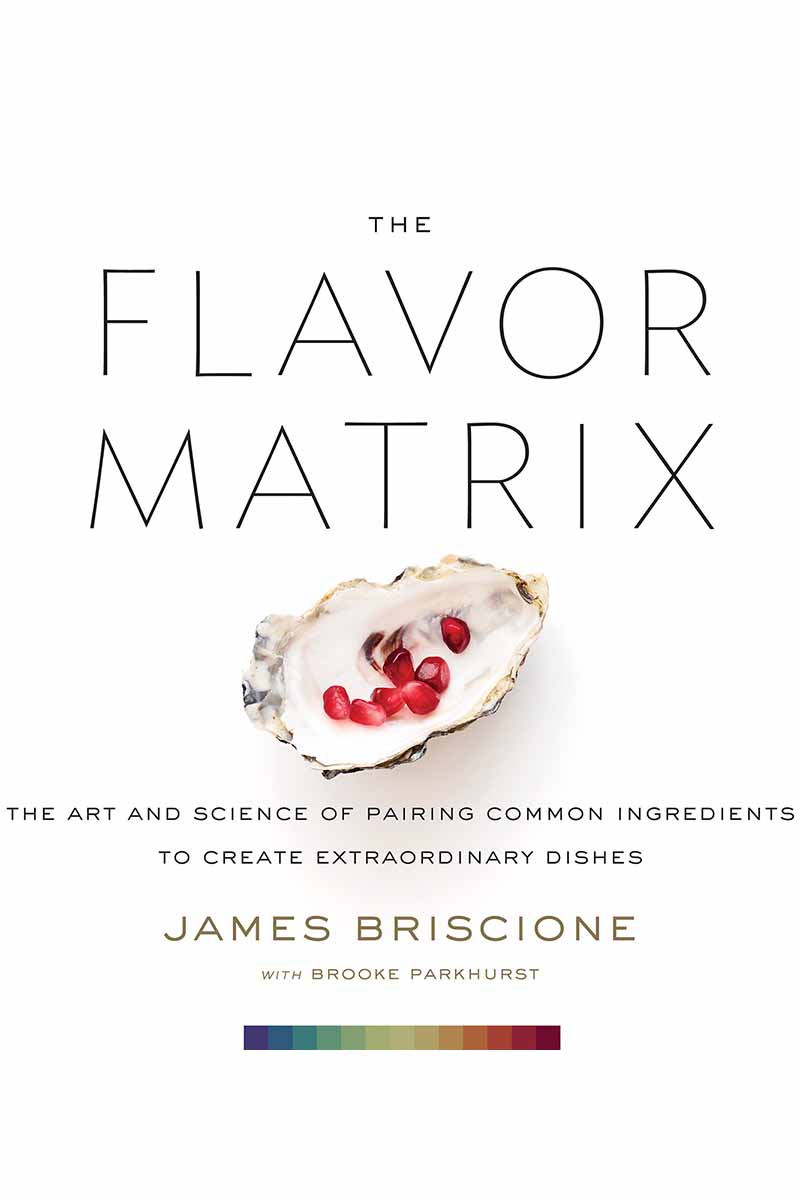

When I discovered that Chef James Briscione was releasing a book with Brooke Parkhurst about the science behind compatible flavors, I knew I’d found my next read. The full title of this book is “The Flavor Matrix: The Art and Science of Pairing Common Ingredients to Create Extraordinary Dishes.”

The Flavor Matrix, available on Amazon

“The Flavor Matrix” began in 2012, when celebrity chef, two-time “Chopped” champion, and Director of Culinary Research at the Institute of Culinary Education (ICE) James Briscione was approached by IBM with an unusual project:

The supercomputer Watson would produce lists of flavors that should scientifically pair well together. The ICE chefs would create dishes based on those combinations, to see how they worked in the real world.

Briscione’s curiosity was piqued, he agreed to participate, and the experiment began.

Watson turned out some unusual pairings. Blueberries and horseradish? Strawberries and mushrooms? Coffee and carrots?

It didn’t seem like these should work, but they did, and Briscione realized that Watson could revolutionize the way cooks combine ingredients.

An Interview with James Briscione

I was hooked on this book from the first page to the last, and I had several questions for Mr. Briscione. Happily and generously, he was up to answer them!

Taylor Shaw-Hamp: This book very clearly communicates your excitement about collaborating with IBM and everything Watson has produced. In the introduction to “The Flavor Matrix,” you mention your skepticism about the Chef Watson project, and yet you said yes to the opportunity. What was the first thing that happened in collaboration with Watson that made you excited about the possibilities of this project?

James Briscione: The first time we worked with Watson in the kitchen I was immediately taken by the way it was processing information and making decisions about ingredients in a dish. It was that piece that really struck me and served as the inspiration to create “The Flavor Matrix” – Watson was “looking” at ingredients in a way I had never considered. We were looking at the components of flavor in ingredients – some perceptible, others hidden. Learning to understand food this way forced us to rethink the entire process of creating in the kitchen.

TS: Watson turned out a lot of flavor combinations. Were there any food combos the ICE chefs were absolutely unwilling to attempt?

JB: Ha! No, that was the spirit of the project. We were willing to attempt anything that Watson suggested, though we did have the latitude to cull through results to find the combinations we found most intriguing.

TS: When was the moment you knew you wanted to turn this experience into a book?

JB: Very quickly. It was so exciting for me to see this new approach to cooking and creativity. I wanted to read and learn more about it, but I found that there was very little information available on the topic of flavor pairing, so I knew I had to create it.

TS: When you first pursued the culinary arts, did you expect you’d be so involved with chemistry and computer science?

JB: Not in a million years! I became a chef because had no interested in medical school (I was going to go into sports medicine). I never thought all this chemistry would be coming back to me.

TS: Following up on the last question, how have you felt about the experience of working so deeply with food science and computers?

JB: I’ve really enjoyed it. It is a challenge that has really stretched me as a chef, forcing me to think about the craft of cooking in new and different ways. More than anything, it pushed me out of my comfort zone and made me stop at every turn to reconsider the ‘why’s” and “how’s” of the tasks I was used to doing every day.

TS: Now that you know what can happen with computers, chemistry, and food, what do you think the future of culinary arts will look like?

JB: It’s all about information and having access to information. It’s fuel for creativity. When I can spend less time thinking about and selecting ingredients for a dish, I have more time to think about how to transform them into something amazing on a plate. We’ve already seen books like “Modernist Cuisine” bring the conversation of science into the kitchen. I hope that “The Flavor Matrix” will continue that, and bring the chemistry of flavor to chefs.

It was amazing to have this opportunity to exchange ideas with Chef Briscione, and hear a little more about how the book came about. Speaking of which, how about I go into some of the details of the book?

The Book

The Introduction to “The Flavor Matrix” provides a satisfying overview on the basics of food science. It begins with a question: how does this modern, pro-gastronomical civilization create new and delicious dishes?

We absolutely can create new dishes – more food is available in the United States than ever before, both through grocery store distribution and the nearly 500% growth of farmers markets across the country.

But that’s precisely the issue. The variety of ingredients available is nearly overwhelming, however, our taste memory – recalling flavors from memory and determining if they go together – is limited. Imagination can only stretch so far, and we can’t combine flavors if we don’t know what some ingredients taste like in the first place.

I experienced this exact conundrum just a few short weeks ago: I’m not terribly familiar with the Jerusalem artichoke, so I couldn’t be certain it would work as a substitute for celery root (for the answer, see page 215 of the book).

Enter: Watson. This supercomputer used aromatic compounds in food to determine if flavors would be compatible or not.

Flavors, Briscione tells us, are not just tastes, even though we tend to use the words “flavor” and “taste” interchangeably.

If we break down what makes up a “flavor,” the results would be comprised of about 20% taste (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami, and fat), and 80% aromatics (how the food smells), with a relatively miniscule quantity contributed by texture.

Watson takes the flavors – these compounds – and calculates the likelihood of compatibility.

Briscione now had pages upon pages of data on volatile and aromatic compounds in foods that were compatible, to varying degrees. Happily, there was already a scientific theory in place to apply this raw data.

As he states in the book, the Flavor Pairing Theory determines that “if two ingredients share significant quantities or concentrations of aromatic compounds, they will likely taste good together.” Armed with this theory and all the data Watson delivered, Briscione went to work.

The rest of the book’s introduction breaks down how to pair tastes (sweet, sour, salty, etc.) and groups flavors into ingredient groups for ease of categorization and application.

For example, garlic, onions, shallots, leeks, scallions, chives, and ramps share very similar aromatics, all derived primarily from sulfur compounds. Since these flavors are so closely tied based on the similarity of these compounds, this group of ingredients is referred to as one ingredient – Alliums, the plant genus to which they belong.

Reading through the introductory sections on these topics plus the overview of how to use the book is a must.

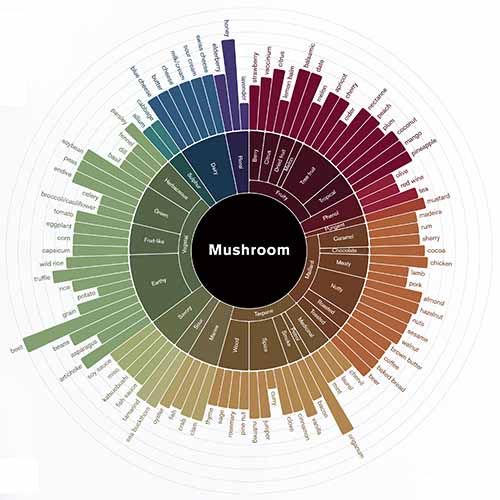

The next section, Ingredients, comprises the bulk of the book, and this is where you will find the flavor matrices referred to in the title.

Organized similarly to an artist’s color wheel, each common ingredient is featured at the center. Working out from this point is the ingredient’s unique flavor matrix. Color-coded by flavor and measured visually to varying lengths, each flavor matrix demonstrates the best compatible ingredients for the main ingredient.

It’s a work of art.

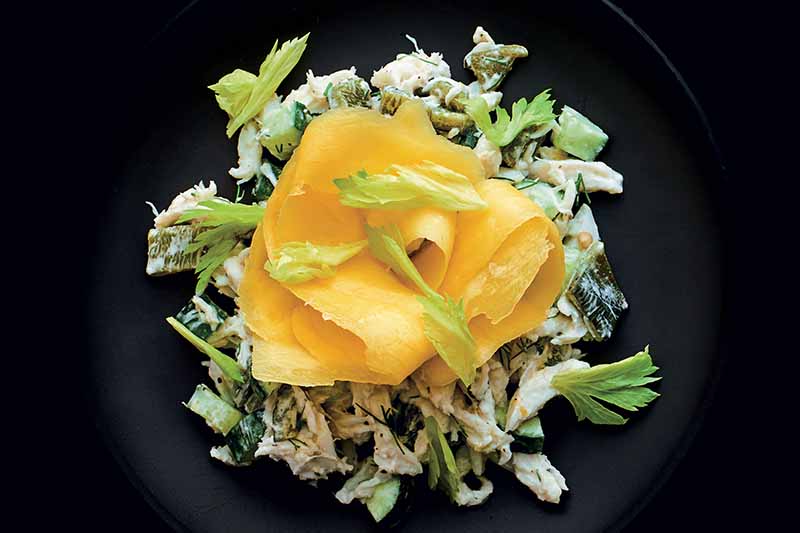

After each featured ingredient is a brief recipe that utilizes it in a non-traditional pairing. These kitchen-tested-and-approved recipes are unusual, yet magnetizing, drawing the reader in with names like Coffee and Five-Spice Roasted Rainbow Carrot Salad, or Porcini, Hazelnut, and Chocolate Torte.

Yes, you read that right. Mushrooms in a chocolate dessert!

Scanning through the ingredient lists on offer can be jarring, but after the initial shock wears off, logic sets in: salty pairs very nicely with sweet – it’s why we dip fast food French fries in ice cream. Since this is the case, is it really that much of a leap to flavor peanut brittle with fish sauce?

The back of the book, the Inspiration section, contains even more reference material. It expands upon the information presented in the introduction, such as delving into the six basic tastes, and lists the most commonly found aromatic compounds, complete with molecular diagrams and flavor notes.

There are several pages of Taste, Primary Aromas, and Flavor-Pairing Charts for Each Ingredient, which offer a shortcut to some of the cross-referencing of ingredients described in the text.

Finally, and most helpfully, there is a comprehensive index. I’ve found this comes in handy for the new reader to become familiar with the various ingredient groupings.

The Verdict

Knowing the recipes have been vetted by experts, I wanted to see if the formula could stand on its own in my kitchen.

I chose a few ingredients that I typically enjoy, and cross-referenced them in the book to verify that they were compatible with each other on their own flavor matrix. These all checked out as technically compatible: cauliflower, citrus, lemongrass, fresh dill, and olive oil.

First, I broke up half of a cauliflower into florets. Next, I chopped about a tablespoon of fresh dill, squeezed out two teaspoons of prepared lemongrass paste, and juiced a lemon into a measuring cup. Then I drizzled in extra virgin olive oil while I whisked, and seasoned it a bit with salt and pepper.

I poured the vinaigrette over the cauliflower, tossed it all together to coat the florets, and laid them out on a lined baking sheet to roast.

Here’s the consensus: lemon, lemongrass, dill, and olive oil on cauliflower works. The formula works. I was so delighted with the flavor profile of this roasted veggie dish, and eager to try more combinations.

I moved on to try a few of what I thought were even weirder combos, because instinct told me that they couldn’t possibly work.

A pork chop stuffed with dill, apricot, and apple chutney? Turns out, it’s rather tasty. Roasted chicken with nectarines, basil, shallots, and olives? Again, the flavors worked together!

Would I make either of these dishes again? The truth is, I’m going to have to pass. I’ve found that I prefer to cook with what I consider complementary foods rather than flavors. But they weren’t complete bombs, and I enjoyed experimenting. I was surprised at just how edible these dishes that I created were. The science is sound.

All in all, I love this cookbook. The food science nerd in me geeks out like a kid in a candy store whenever I flip through these pages, and I can’t imagine getting tired of it any time soon. I find the suggested flavor combinations to be challenges to be conquered, and I’m looking forward to testing some of the suggested recipes.

Do you think “The Flavor Matrix” is for you? Read what others have to say this book and check current prices on Amazon.

What wacky flavor combinations will you try first? Tell us about your taste tests in the comments below!

Photos © Andrew Purcell, James Bricscione, and Hougton Mifflin Harcourt, reprinted with permission. See our TOS for more details. With additional writing and editing by Allison Sidhu.

About Taylor Shaw-Hamp

Taylor Shaw-Hamp has loved food ever since she can remember. The more she grew, the more she discovered, and the more she had to know. Now she loves to write about her food adventures through recipes, product reviews, and blog posts. She can be found at local coffee shops across the world, so if you see her, stop by the table and say hi!