Want More Delectable Episodes? Subscribe to our Podcast!

If you’d like to receive the Foodal podcast episodes on your favorite devices, subscribe with your preferred method below:

Shownotes

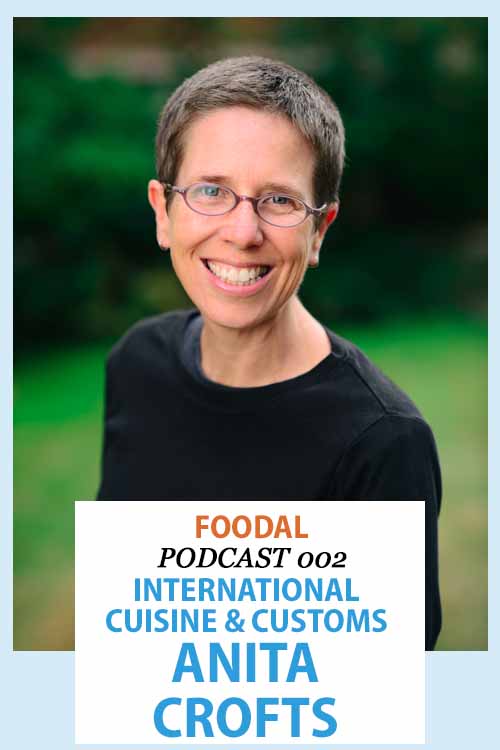

In this episode of the Foodal Podcast, managing editor Allison Sidhu interviews Anita Crofts, author of the book “Meet Me at the Bamboo Table: Everyday Meals Everywhere.” Join us as they discuss:

- Cultural understanding and expressing cultural identity through food

- Sketchnoting and documenting our meals with photos

- Shared meals and cooking with love

- Pie! And tips for cooks at the holidays, when faced with that big family meal

- The importance of travel, from the everyday to the around-the-world journey

- The fabulous food and region of the world that Anita would love to explore someday

Plus a look at kitchen gadgets and beloved cooking tools, foods from around the world, and more about Anita’s wonderful new book!

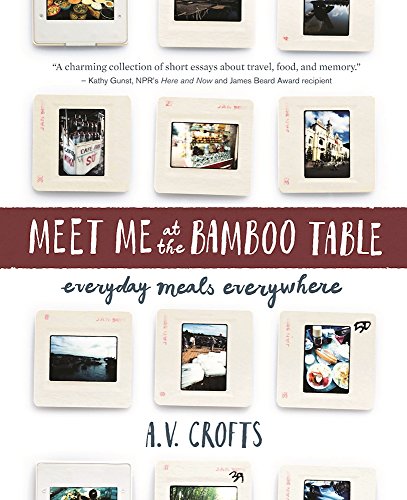

Meet Me at the Bamboo Table: Everyday Meals Everywhere available on Amazon.

Transcript:

Allison: I’m Allison Sidhu managing editor at Foodal.com, and today I’m speaking with Anita Crofts, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Communication and a Clinical Instructor in the Department of Global Health at the University of Washington, as well as author of the book Meet Me at the Bamboo Table: Everyday Meals Everywhere. Thank you so much for joining us today, Anita.

Anita: Thanks, Allison. It is so good to be here.

Allison: Well, I want to jump right in. So, your book, it documents your journey around the world through food. Tell me about writing Meet Me at the Bamboo Table and why food was the lens through which you chose to tell these stories.

Anita: [Laughter] I love to eat!

Allison: Yeah.

Anita: And so let’s start with that. I mean I’m always someone who is thinking about my next meal, and I think for me I’ve always appreciated not just the act of what food represents or the act of eating so much, but really enjoying how food can become a terrific bridge when you’re thinking about cultural understanding, or getting those windows into how societies work, or what makes a person tick. And to me, what we eat is often an expression of who we are.

And so to think about putting together a collection of personal essays, it seemed right and good that food be at the center of how I considered what we think about when we think about what makes up a particular community or what makes up a particular person. And food just seemed like a natural expression of that.

Allison: Right, definitely. Something really interesting to me was that the pictures and the stories in your book don’t appear in chronological order, or geographic order, or even the order in which we take our meals throughout the day usually. To me, if I had to say there was any discernible order here while I was reading, it was more like the way memories bubble up in our own minds, like when a certain taste suddenly takes us back to a place we visited once, long ago. Tell me about the way that your book is organized and why you made these choices.

Anita: I actually wrote the book chronologically. If you were to go into my computer and look into my files, you would see that I started with the Wisconsin essay when I am seven years old and I finished with the essay from Turkey and Syria, which just took place last year. And it made sense to write it chronologically. But then, as I started to have conversations with the graphic designer that I was working with, with my wonderful publisher, and some of the editors that Chin Music Press provided, we began to consider whether or not we really wanted the book to run chronologically.

And I think part of what inspired the decision to make it as you say, more of a – it’s almost more of a buffet, you know, to use this terminology, almost a potluck of when you open up the book – is that part of our vision was that the book would be such that you could pick it up for five minutes or you could pick it up for five hours and it didn’t matter what page you cracked open, but you’d be able to fall into an essay where you’d learn something. And the idea of having that flexibility was really attractive to me.

Also, I felt that there was something to be said for not conforming necessarily to the rigidity of chronological order. That there was something to be said for having the stories, like you say, bubble to the surface in different ways, in ways that memories can sift and rub up against each other in our brains very rapidly. We could be thinking about something from childhood and then we get zoomed back into the present tense very quickly.

And so I wanted the book to be able to honor that kind of dynamic and elasticity of time, and I felt that if we worked hard to make each of the essays live in some way autonomously, that they could be connected through my voice and connected through my experience, but that the reader would be able to enjoy them even if they didn’t unfold in a linear fashion. That each of them to some extent was a story unto itself, and even though I’m the common denominator in my experiences there, I really appreciated the opportunity once I had the – it was really quite close to being the final draft of the manuscript – being able to then decide, maybe like musicians look at a record album, or we think about a meal too, that there’s – I really worked hard to put them together in an order that made sense to me.

It wasn’t like I just put all twenty-one cards in a basket and threw them up in the air and said, “Let’s just let them fall as they may.” I really did think about where I wanted each essay and how I wanted them threaded together. But I appreciated the opportunity to come at it from a different lens than chronology.

Allison: Yeah. I really like that this is a personal memoir, it’s a collection of different vignettes from things that you’ve experienced and different meals you got to have, but there’s also a bigger picture here, and I feel like there’s a bigger message. So there is a story that you tell when you are in China in 1991 and you say, “You never need a fortune to eat like royalty.” And there’s this other quote that stuck out to me where you say, “Pickles pop up just about everywhere. Their universality makes them culinary touchstones that bridge cultures and translate across tastes. Ultimately, it is our shared appetites that bind us.” And I know this is a huge topic, but I want to get your take on this.

In addition to being this personal document that explores your memories through food, I think your book is also an expression of cultural awareness, where it touches on deeper meanings of eating across cultures and sharing food with others, and that eating is for everyone, and you know, it’s something that everyone does. Why is it important to tell these stories, and what can we learn from them?

Anita: Yeah, absolutely. When I think about what has shaped me over my life and the way in which I walk in the world, one of the real abiding hopes that I had for putting together this book Meet Me at the Bamboo Table was to speak about what I hold very dear, which is the importance of mutual understanding, mutual respect, and appreciation of difference. A celebration of how much we can not only learn from one another but, to use the example that you gave with the pickle quote, that there are, I believe very fundamentally, some universal emotions and connections that people make regardless of what culture they come from. And that can happen within one country, and that can happen across countries. And so I felt really quite committed to this book expressing larger philosophies I have about the importance of that kind of cross-cultural understanding.

And back to your first question earlier in terms of why food, to me food was so often that ability to feel a little bit closer, to get a sense of welcome. Food was able to represent, in some cases, language when language wasn’t necessarily something that I shared with another person, but food was able to be that bridge.

Allison: Yeah, and I also wonder, tied into that, still looking at the bigger picture, where cultural appropriation comes into play when we think about who is making our food, and if it’s okay to do our own spins on different recipes and you know, we have lots of fusion restaurants today. And that word that so many food writers like to use, “authenticity,” and how that comes into play related to your own stories, and what you’re trying to share through your book.

Anita: It’s a very important issue, and I’m actually really pleased that there’s a growing chorus of really sharp writers and really deep thinkers to consider what we experience when it comes to food that’s either prepared for us or food that we prepare, or the way in which food and cultural identity is presented. Because I think it’s really important that when I – for instance, for myself, considering putting this book together – I think the reason that the personal narrative and the memoir was really vital is that I wanted to make it clear that I was speaking for myself in this book, and that I wasn’t trying to suggest that spending six days or seven weeks or even a year and a half in another culture allows you to consider yourself an expert on that, on somebody else’s lived experience.

And so to me, the anchoring of the book in personal memoir was just a reminder of that at the end of the day, I can speak for myself and I can speak for my experience, but it’s not my place to speak for others. It’s more, the expectation is that I can make observations and that I can try to then tie those observations to my own lived experience. But it really is important.

There’s a tone, there’s a language, there’s an expression of really articulated respect around what particular foods might mean to particular cultures, and not wanting in any way to diminish the contributions that they’ve made, or the ability of these individuals to receive that kind of recognition for the food that they produce and what it means to their identity. So to me, it’s an important recognition for all of us, whether it’s within our own countries or as we travel overseas, to consider all the various stories and identities, and a sense of real personhood that exists in a meal, in a kind of food. These are very real emotions and I think we need to be very cognizant of them.

Allison: Definitely, and nothing happens in isolation. We live in a very global world and there is so much that we can learn and experience, and food is a great way to do that. I think we could continue talking about this topic forever. [Laughter] I’m going to shift a little bit.

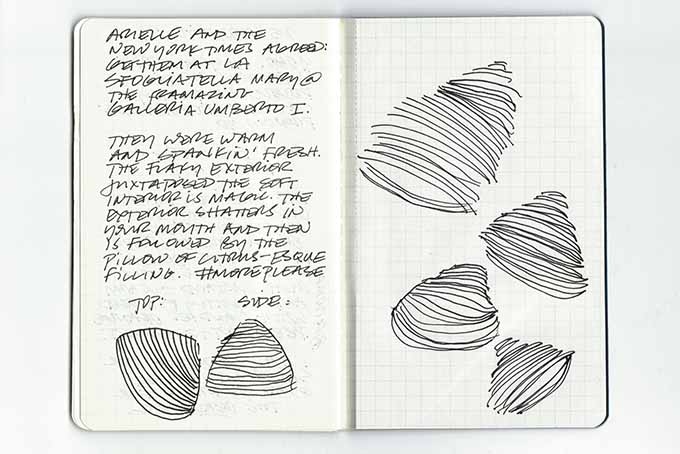

So, another really great thing about your book is the wonderful photos, and the way that you also included some of your own illustrations. At one point you say, “Sadly, all good meals must end. But meals can be logged for posterity in many ways.”

So you talk in the book about sketchnoting and I was really delighted to see your own sketches of meals that you enjoyed in Italy. Sfogliatella, I don’t know if people are familiar with this pastry, but I guess you and I both love it. It’s basically shaped like a seashell and wrapped in this very thin pastry that kind of shatters when you bite it, and there’s this light, citrusy cheese filling. And I just love that your pictures there, they just bring something else to mind when you combine that with the words and with the photos. How does drawing help to enhance your memory of food and what does that activity mean to you?

Anita: Well, I love the intentionality of it. To me, there’s something that just sort of spells adventure when I have a reporter’s notebook in my hand and a pen in the other. And it brings a level of ritual to eating that I really enjoy. And it’s not that it has to be out at every meal, but I really appreciate that, as much as we might want to imagine that our memories are vaults, it’s amazing how much we lose over time.

Allison: Yeah.

Anita: You know? In the moment it feels so vivid and it feels like it will never abate – that sense of this moment, how it smelled, what it tasted like, and who I was with or where I was in the world – but we know that the passage of time is something that happens to all of us, no matter how keen our sense of recollection is. What I also like about being able to document things is that it is amazing what we forget, or what we can’t resurrect as easily. And so the sketches, as I said, they lend a level of archiving that I know I can go back to. And with just a bit of a prompt, whether it’s – as the picture in the book of the sfogliatella from Italy suggests – all I have to do is take a look at those two pages, and I’m right back in Naples.

But I need that as a – it almost becomes a visual portal back to a memory, that I know that this prompt is going to get me there faster when I am able to look at it. So it’s not only for my own enjoyment in the moment – and that ability to actually translate an experience onto a page, that’s very much a part of it. But it’s also for my enjoyment down the road where I know that eventually it’s going to become a really necessary prompt to help me to get back to that memory. So, it’s like creating a visual breadcrumb, you know, a path for myself to go back to that particular time, which I really enjoy.

And it also, to me, I love that decision – what am I going to draw, how am I going to draw this? How am I going to take this experience and put it onto the page? And sometimes it’s a more formal laying out of all the various elements of a meal – there are some examples of that in the book. But then other times, like this particular one with the pastry, it’s a very spontaneous sense of, “I’m just going to document what it looks like and note it.” But it doesn’t need to be formal and it doesn’t need to be what some people might look at and say, “finished.” It’s the act of documenting it that really puts you in that moment, and then can take you back to that moment in the future.

Allison: Right. And then the photos on the other hand give this sort of different sense of permanence. There are parts of your book that I spent a lot of time poring over that are almost like an Instagram feed, with photo collages with all sorts of bright colors and street scenes and close-ups of plates of food, and these don’t have any captions. And I think they can be read within the context of the stories that surround them on the following pages, or they can even be enjoyed and explored on their own. I was wondering if you could talk about this choice to put them in the book this way, but also about what seems to be our growing obsession with taking pictures of our food.

Anita: [Laughter] Yeah. That’s so true! And I’ll get to that, I’ll get to your second part of your question in a minute.

Allison: Yeah.

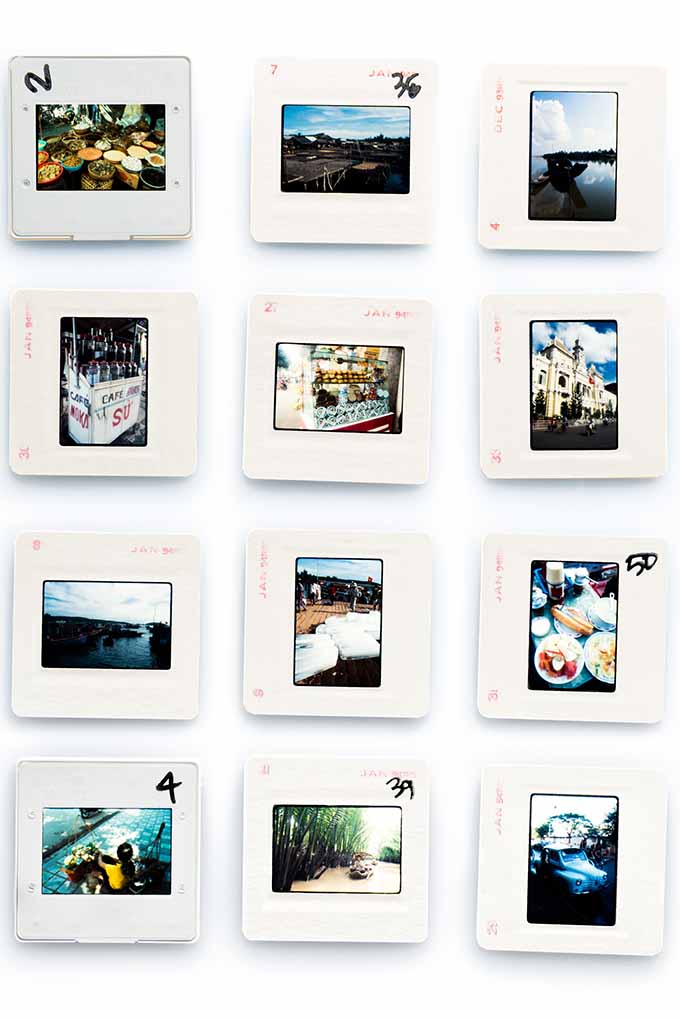

Anita: But to the aesthetic considerations around “how do we want to weave photographs through the book?” We knew from the outset that it was going to have a strong visual component – that was important to me, and it was important to the Press. And it was interesting how over time, the way that I had documented my travels had shifted. I mean, the cover art is actually slides I took in Vietnam in the nineties, and there are certain photographs that are in the book that are digitized of prints, or then there are other photographs that were absolutely digital from the outset. You know, some of the more current photographs in the book I have snapped on my phone and they probably went up on Instagram, if not thereafter. So it shows this interesting evolution in the way that I actually take a photograph and think about photography.

But the intentional choice around not putting captions was one that Dan Shafer (the graphic designer) and I spent some time really considering. We wanted there to be, how do I put it? We wanted the experience of the reader with this book to be such that even though it was very much my personal essay and memory and an experience that I had, to tap back into that sense of the universal messages of the book, whether it’s around shared understanding, growth – thinking about the role that we all play in the world, and what mutual understanding and joy and delight and the experience of new adventure looks like. And really, the considerations we all make in terms of how we grow and how we define ourselves and what that looks like.

In keeping with that idea of universality, by not having captions, we really wanted to allow the reader to experience the photographs and to some extent conjure up their own stories around them. We didn’t want to be as prescriptive and say, “this is a photograph that reflects either this particular part of the essay,” but instead allow the reader to form their story and their connections based on the prose, but then also their own experience of those photographs. So it was a way to invite readers to put themselves into the book a bit and experience those photographs without any prompting on our part, or on my part in particular, to say, “this is what this is a photograph of.”

There’s a lot you can infer from the text and make those connections, but I really wanted there to be a chance for the readers to experience, to some extent, on their own, and make those associations themselves. It seemed to be a freedom that I wanted to provide readers that, as I said, aligned with that idea of, there’s some universal themes to the book that I wanted them to absorb.

Allison: Yeah, so building off of that – I’ve got to say for me, one thing that I wished while I was reading was that your book included some recipes as well. And that sort of is a counterpoint to what you just said about this, you know, more of the freedom to explore and build your own interpretations. But, for me, I’ve been cooking since I was three years old, and I still have recipes that I know by heart. But you know, every year when I’m ready to make something for the holidays I still pull out a copy of my great-grandmother’s recipe just to see it written down and follow it. And you know, especially when I was reading your stories about making dumplings and pie – and we’ll get back to pie a little later, I promise – but I wondered if maybe you chose not to make this into a cookbook for a reason. What do you think?

Anita: That’s a really good question. I mean part of it is, I – you can ask any of my friends, you can ask my family – in general, I cook without recipes. I tend to be pretty improv, sort of stare into the fridge at night and say, “Okay, what’s going to happen tonight?” And that’s not to say that I never crack out a recipe – I actually have been known to keep cookbooks on my bedside table, I enjoy reading them so much. But I think temperamentally, I tend to be more along the lines of improv when it comes to cooking. So I think just from a – my predisposition wasn’t so much along the lines of providing a recipe.

If I can consider it from different angles though as well, I think part of it is – and this gets back to that question around identity and appropriation – to some extent a recipe becomes a snapshot, and it also becomes – there’s a rigidity to a recipe as well. And sometimes for very good reason. I mean, we’ll talk about this when it comes to baking, but it took me a long time and many recipes to get to a point where I don’t really need a recipe anymore for baking pie. That’s not – you can’t just expect someone to bake a pie without a recipe right out of the gate, that comes after a lot of working with recipes. So I certainly understand that.

But I do think that in this particular kind of design for the book and the image that I had in my mind, there was something in it that I think is related to the captions. That to me it’s, it was not wanting to necessarily say “here’s the way I do it” in terms of a recipe. That was a bit more – that was a level of granular detail like a caption that just didn’t feel like it fit the aesthetic quality of the book. Again, could be that’s in general just my predisposition, but I think it also was a larger vision that we had for the book itself. And also knowing that on the one hand, you can’t be all things to all people, and so I had to decide – I mean, it was already crossing a lot of different genres. Like, where’s a bookstore going to house this book? Is it going to be in travel, is it going to be in food, is it going to be in memoir – straddling a fair number of them? I think throwing in recipes perhaps just felt like it was adding one more element to an already crowded collection of different genres.

Allison: Yeah, I totally agree. That idea of rigidity with recipes, especially with beginning cooks, you know, you’re very cautious about how do I riff on this, do I need to follow it by the letter? And I love that idea. I think it is something that I have worked on teaching people myself, of just looking into the fridge and seeing what you have and saying, “What can I make tonight?”

And this reminds me of one item that you mentioned just briefly from your experience in China in the early nineties. You talk about these restaurants in a part of China where the growing season lasts throughout the year, and you said you found that rather than ordering off of a menu, the customers would actually scan the shelves and take a look for themselves at what had been brought in fresh from the market, and they would order based on the ingredients that were available. And you mention that this inspired new combinations of ingredients in a way that a structured menu wouldn’t allow.

But this really made me think about the way that a menu also gives the chef a sense of control over what’s being served and what they want to put out there. And that the sort of system that you described is so much more of really an open conversation between the chef and the diner, one that’s a lot more like what you were talking about, what we do experience at home looking into our own fridges. So, do you think more restaurants should adopt this, and what does it say between – what we usually see as the differences between eating out and eating at home?

Anita: Yeah, I loved that tradition that you mention from Yunnan province down in the southwest part of China where lots of the mom and pop restaurants, they just, you know – no menus on the table, you walked into the back kitchen, and the wait staff or in some cases the host that was also perhaps – so you know, maybe a two- or three-person operation – would walk with you along the shelves and you’d kind of take in what was there and then make those combinations. And I could remember, there were times we would order things that were very common, that were dishes that were really familiar to the proprietors and ones that we had been introduced to by living in that environment. And so those were always met with, you know, nodded heads and like, “Okay, yes, of course you’re going to get that, you’re going to get that.” But then there were also times where we combined things, and I remember sometimes getting some chuckles or a confirmation like you know, “Do you really want to put those two things together?” [Laughter] And we would say, well, you know, “How about give it a shot?” And most of the time people were very game, they would just confirm.

And to me this also relates to that idea of appropriation, because to me the other side of the coin of honoring where food comes from and what it represents is also honoring the inevitability of adaptation. We know that crops, that cuisines, that individuals – that we move. We are a world of migration. Internal migration, and also across countries. And so what that inevitably means is you’re going to have collisions of different food traditions. And what I’m discussing about being in a little tucked kitchen in Yunnan province is one small example of me bringing my palate to the way that I might combine traditional Chinese ingredients. But I find that really exciting. To me, there is something wonderful about what we all bring to an eating experience, and the way that we experience different foods.

And the fact that I could walk thorough parts of Southwest China knowing that things like potatoes and things like tomatoes, that were so ubiquitous and in so many different dishes, were introduced crops. And yet, they had been introduced to wide acclaim, and have been now fully integrated into treasured menu items. So, I really appreciate that evolution of taste, and the way that we can adapt and we can change and we can approach different tastes in different ways.

Now, getting back to the question about the way that restaurants can engage, or the dining experience and the role of menus and the role of control – I mean, I perfectly understand that there are restaurants out there where, what I’ve described from Yunnan province sounds like abject chaos [Laughter] because there’s, you know, you have to have a certain supply, and the idea of opening up your kitchen to diners and saying, “Hey, can you throw that together?” I mean, it can happen at a smaller scale.

But I will say that, you know, while I appreciate sometimes being able to go into a restaurant and there’s a real mindfulness that has been put forward in the menu and you really get to – I mean, the menu itself becomes a bit of a story because it’s an expression of the chefs and the vision around the restaurant. And I deeply, deeply appreciate that. But I also think there’s room, and it would be exciting to see more of a movement to – it’s a form of customization, I suppose you could say, that it allows diners to have a sense of, okay, here are the broad sweep of ingredients, and now it gives you some ability to say, “How would you like to mix and match them in a way that works for you?” Because that customization really worked well when I was in that part of China, and it seemed to create very satisfied eaters.

Allison: Yeah, and I think it really draws in imagination, which I think, like you were getting close to saying before, that also for the way people can interpret your book and skip around and look at the pictures and read the words and get different experiences from that, that they tie into their own experience.

You know, I wish your book had scratch and sniff or some kind of Smell-O-Vision [Laughing] because I felt like that was the one sense, that I really wanted to experience that part of it. And it’s so important in food that we are getting all these things from all of our different senses. And it is all tied together, and tied to our memory, and tied to imagination of what we might get to eat, you know?

There’s one part in your story about your visit to India in 2003 where you talk about the importance of really diving in, and being alert to the experience of what we’re hearing and smelling and feeling, as well as what we taste, when we’re cooking and eating. And you say, “Like India itself, cooking required all your senses. Watching for onions to become translucent. Listening for the pop of mustard seeds. Tasting stew for salt with a dipped finger.” And you say that you honed in with this sensory intensity. So what can we take away from that as, you know, from beginner cooks and eager eaters to maybe even more advanced chefs in the kitchen?

Anita: I would say, you know, always approaching the kitchen with what one of my colleagues refers to as “the eyes of a traveler,” because if we approach the kitchen as if we are travelling, and we think about the mindset and the level of observation and the level of excitement that often we bring to travel – whether it’s heading out for a weekend getaway right in your own backyard or actually packing that passport and going, you know, thousands of miles away – I think approaching the kitchen with that same sense of not only discovery, but also being wide open to learning.

Because part of really experimenting in a kitchen and becoming comfortable with different combinations, and how things work, and what it means to apply heat, and why do we bake things this way, and why do we combine ingredients in this way, and how can I become a bit more fearless in terms of putting together different things, and if I don’t have all the ingredients what can I substitute, and how can I train myself to think about substitutions where it doesn’t create stress?

If anything, it creates this wonderful game for ourselves of how do we, you know, how do we triumph in a kitchen where, like life, we’re never going to have all the answers? We’re never going to have everything all put out in front of us. So, there’s a level of being able to be adaptable and being grateful for an opportunity.

And that, to me, is all so connected to travel, which is I think why the nature of this book combines food and travel and eating. Because to me, there’s much to be learned from that mindset – that mindset of being open, that mindset of being keenly observant, that mindset of being a bit more fearless, the way sometimes we are when we travel.

We take risks when we’re in a different environment because I think we feel a level of liberation that the preconceived ideas of who we are don’t hold in the same way. And I’m not talking about being reckless, more that there’s a level of confidence, I think, that comes from putting ourselves in new circumstances. It prompts us and prods us, I think, to be, as I said, just a little bit more courageous around opportunities that we take.

And I think marrying that same kind of attitude, the attitude of a traveler – taking notes, being a sponge for what’s happening around us, having all of our senses on high alert – that works so well in the kitchen for so many of the reasons that we’ve talked about. Whether it’s – how does an onion smell when it’s at the point where you should add the other ingredients? What’s the consistency of this stew? Why is it important for the pie dough to rest before I roll it out?

I mean, there are things you can touch, there are things you can taste, there are things you can smell, and things you can hear. And all of those senses go into the way that we act in a kitchen, and how we feel about engaging with food as we prep it in the kitchen. And to me, the connection with travel is a really illuminating one.

Allison: Definitely. And, you know, you mentioned baking. And I think baking can be really hard for people because there isn’t as much room for that experimentation. You can’t really taste as you go along, and a lot of people are very cautious about that. But I think a lot of people are driven to it because we have this love for comfort food. And so many of the foods – especially in the US – that people go back to, that maybe family members made for them, are pies and cakes and casseroles that were baked in the oven. So, I’d really like to focus back on that pie that I mentioned earlier.

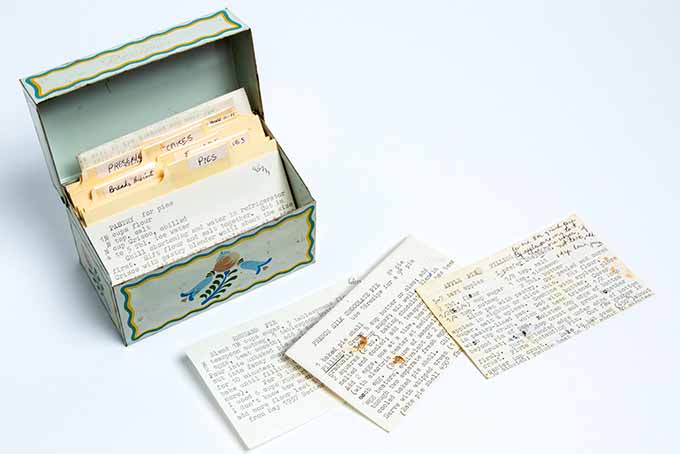

You have a section on your website pepperforthebeast.com where you list ten things about yourself. And number ten is “I bake a mean pie.” And I was like, I am right there with you! [Laughter] And you know, there’s actually a section of Meet Me at the Bamboo Table that’s about pie where you tell this story called “The Problem with Crisco,” and you even include this great photo of the box of recipes that your grandmother gave you, all typed out. So why has pie played such a significant role in your life, and what do you love about it?

Anita: Well, I love so much about it for a number of the reasons you mentioned. It’s, to me, one of the ultimate comfort foods. And I think one of the reasons it’s an ultimate comfort food for me is the fact that there was this wonderful tradition in my, on my mom’s side of the family where my grandmother was an exceptional pie maker, my mother is an exceptional pie maker, my aunt is an exceptional pie maker. And I talk about it in the book as being my inheritance. [Laughter] That it’s almost as if genetically I was meant to make pie.

And I could not agree more – baking is very unforgiving. I may like to be an improv cook in the kitchen when putting dinner on the table, but it took me a long time to get to the point where I felt like I could riff a bit on pie recipes. Because in the beginning there’s a reason for that specificity, and that real clarity in a recipe. And to me, part of the alchemy of baking is that you’re putting together all these interesting ingredients, and if you do it to the degree and with the ratios that are expected, you’ll get this just magical response in terms of putting together – I mean a pie itself doesn’t even have to be that many ingredients, but if assembled in the right way and then placed in the oven and baked at the right temperature, you get something just quite extraordinary that comes out of the oven at the end of the day.

So, for me, pie was not only familial and to me one of the earliest expressions of love – earliest expressions of love – was the fact that when my family would clamor for a pie, my grandmother would answer that call. To me, it was a way that she put something on the table that was not just an expression of love, but also an expression of wanting to make those that she loved happy. So, the way that we would just all champion those pies and look forward to them, I sort of joke that our family eats our dinner so quickly because we know that pie is coming. [Laughter] You know what I mean? It’s like, can we just get to dessert?

And we’re talking – I mean, yes, of course there were certain meals where one pie might be there but it was often this incredible – you know, she had many pies that she baked very, very well and of course over time people would also, you know, like my mom would bring one, my grandmother would bring another, my aunt might make one. So, it was always a bit of a roster that made for different tastes for different people. Who likes minced pie? Who doesn’t like chocolate pie? Who really wants apple? How many pumpkins do we need? That kind of thing.

And I think that to me, that expression of what it means to bake or to cook for your family, we all have those dishes that when they arrive on the table, we feel just an incredible sense of comfort because they, there are stories in those very dishes. Where did the recipe come from? When do we typically eat it? What does it mean to us? Why is it meaningful? And to me the answer in that question “why is it meaningful?” is that it ties us to people.

That taste becomes one we associate with the company that we keep when we eat it, and I can make my grandmother’s chocolate silk pie for friends in a different part of the country and my grandmother is nowhere to be seen, but she’s so present in not just the preparation, but also just watching a friend enjoy that pie for the first time knowing that I’ve had the delight in enjoying this pie for many, many, many decades. But to see someone enjoying it for the first time just feels like an extension of my grandmother’s memory. So, that, that feels really good as well.

Allison: Yeah. I – we are so thrilled and honored that you’ve shared your grandmother’s recipe for French Silk Chocolate Pie with us, and we’re going to make that available to Foodal readers on the website. I can’t wait to try it myself. I’ll have to send you a picture when I eat my first bite because that means a lot to me too, to see the look on people’s faces when they try my recipes and food that I share from my family. And it actually reminds me so much of this pie that my own grandmother would make sometimes for Sunday dinners when I was a kid. So yeah, that means a lot to me and I’m really excited to be able to share that with a lot of people, so I thank you!

Anita: Oh, I am so thrilled! And you must send me a photograph.

Allison: I would love to.

Anita: Because this pie is – it’s a showstopper.

Allison: Yeah, it looks excellent. It’s going to be delicious. And I just really like that you said, you know, cooking can be this expression of love. And at this time of year especially, you know, in a lot of places it’s getting colder out, we’re looking for these certain foods for comfort or that we remember from these happy times. And a lot of families are gathering together for the holidays, and there’s a lot of pie baking going on. And we’re talking about everyone from pie enthusiasts like ourselves who are really passionate and have been becoming experts and honing their craft for years, all the way to people who hardly ever set foot in the kitchen except for this time once or twice a year when, you know, turkey roasting and pie baking and big dishes for a lot of people that they don’t usually make or have to worry about kind of rolls around once a year. Is there any advice that you can give, you know, at Thanksgiving and at these big family gatherings for, I don’t know, for pie bakers, for people who might not be used to cooking, anything in between?

Anita: No, absolutely, I mean, the first thing I would say is – I’ll use an analogy. When I was learning Chinese, one of the best things that my beloved Chinese professor ever said to us at the beginning of second year Chinese was, “I want you to speak loudly, speak confidently. You are going to make mistakes, but the only way that you are going to learn is if you apply yourself and you do it with a level of passion and zest, and just know that that is the way that you learn.” And it was such a wonderful message to just invite that high level of engagement and that, that confidence that even if you’re not feeling it inside, her argument was, well you’re going to speak with confidence because ultimately that’s what you’re going to gain.

And I feel the same way when it comes to taking on something like a pie, which I absolutely realize there’s a level of fear factor and it’s legitimate. [Laughter] Pie – you know this too, I mean the, and I talk about this in my book – that when I transitioned from using Crisco in my crust to using butter, in some ways I had to reboot my pie prowess. I mean, it was a – it’s a very different kind of fat. And so I, I had the experience of knowing what I had been able to accomplish in the past and having to retool, retrain myself a little bit. And it was a very humbling experience, but ultimately it was a really good one. Because it meant that I had to be gentle with myself, I had to provide myself that encouragement.

And to know that however it is that you best learn in a kitchen, you should absolutely do that in moments where, especially if the stakes are a little bit higher and you’ve got a big meal that you’re prepping for. And we know that Thanksgiving, for all its joys and the ways that it brings families together, for the folks in the kitchen, it’s a bit of a command performance. And I would encourage people to spread the wealth, everybody helps out – it’s fun, it makes people feel really involved. And so, trying to find ways to encourage a potluck approach that still feels like there’s some, that there’s a theme that runs through it and you feel good about all the dishes that are going to hit the table. But for everyone who may be coming into the kitchen in a way that isn’t so much a natural habit, to encourage everyone to see it as an opportunity to learn, an opportunity to challenge yourself.

But to know that if it’s – like let’s say pie making for an example – there are great recipes out there. Take your time, do a little bit of homework in advance, do a trial run if you want to. Know that there is so much wonderful information out there now whether it’s your tutorials, or talking to friends, or the books that you can dive into. To really see it as an opportunity to learn, see it as an opportunity to bring in information that will allow you to feel like you’ve got as much of a safety net as you can when you’re putting together that pie. And just hear it from those of us that, that putting a pie dough together isn’t something that strikes terror in my heart. But just know that I understand how you feel, and that spending some time thinking about it and taking your time and not holding yourself to such a high standard that it feels stressful.

At the end of the day, putting together a pie is, it’s a bunch of steps. And it’s steps that anybody can follow. And it will work out. And ultimately, because the intention behind what you are making is so good, because you are presenting this to people that you care about, no matter the size of the table, no matter the holiday in question, I really fundamentally believe that our guests at a table are a forgiving and a generous group. And I believe that they will be – that there is so much to be said for the act of even putting together something that is homemade out of a kitchen right now.

Keep that in the forefront of your mind, that that investment of time and love and preparation that you are making, that in and of itself is such a gift. What you end up putting on the table is almost secondary. And obviously, yes, you want the pie to taste wonderful, or you want the turkey to come out moist, or you want to make sure the stuffing is terrific – whatever it is. But know that your guests are there for your company, and the food is secondary.

Allison: Yeah, I definitely agree. It reminds me, there was an opinion piece recently […] It was by A.O. Scott, the cultural critic, in Food and Wine magazine, the recent Thanksgiving issue. And he, that’s exactly what’s discussed. That you know, what do you do when you’ve been telling Grandpa that this stuffing that they’ve been making for twenty years is so delicious and then they try a recipe the next year, and it’s even better? Does that mean that you have to admit that you were just being nice and being grateful before, when maybe [Laughter] you suddenly have this new standard that you appreciate in a whole new way?

But it’s not about that, it’s really about love and appreciation for this gathering of family and friends, and doing this thing together and for each other that you can all really appreciate and remember. And you gain – you eat the food, but there’s also this sense of commensality, which is so important in these shared meals.

Anita: Oh, I totally agree, yeah. Completely agree.

Allison: Yeah. So I think another thing that can be kind of intimidating to people at all levels of cooking is the amount of technology that’s out there and available for us, as far as appliances and kitchen equipment goes. And, something we try to do on Foodal, we provide a lot of reviews of different products and things that we’ve tried that we think are really great, that we want people to know about. I wanted to talk a little bit about kitchen gadgets with you.

There’s one point in the book where you mention a Japanese plastic pickle press that a friend gave you. And I was wondering if you wanted to kind of talk about the role that, what I would call gadgets, kind of play for you. Or what’s one gadget or appliance or piece of kitchen technology that maybe you learned about and didn’t even know existed before, or that you just couldn’t live without today?

Anita: Oh gosh, that’s such a great question. One of the things that happened to me in the last couple of years, and I mention this in the Italy essay, is that I moved from a house to a smaller condominium. I downsized in Seattle because I spend my academic year in Seattle and I spend my summers in Maine. And I have condos in both locations, and so it worked to have these smaller spaces that I occupy in order to be able to have two spaces, if that makes sense.

And what that also means is that I have smaller kitchens. And I have – smaller spaces means smaller kitchens. And so when it comes to what I put in my kitchen, as it does for any small space, you’re looking for a real combination of like a high level of utility and a high level of enjoyment. That’s sort of my metric that I come at it from. Is this something that I use a lot, and is it something that I really enjoy using? And it could be something as simple as my favorite spatula, or it could be something like you mentioned where the pickle press, I might not use that all the time, but it’s a wonderful example of a little – it’s something that’s very simple, and yet it can produce something, to me, that just is so delicious.

Taking a very simple Persian cucumber and adding some salt and some vinegar and then putting it into the press, and then in a couple days having something that just tastes remarkable. I mean, that’s just one of the forever amazements that I have about the way that just a short list of ingredients can produce something that tastes so dramatically different than all of the distinct parts. But when you put them together, it’s that amazing combination that leads to a particular taste.

Allison: Yeah.

Anita: The question of different appliances, I’m sure – I mean, one of the things that I have been thinking about a lot because I use it for so many different reasons is, I have a mixing bowl that was my grandmother’s. And it’s got a bit of a milky glaze, it’s the largest mixing bowl that I have. But I use it for so many different things. It could be that I’m making cookies, or that I’m tossing some carrots in a powdered sumac, or – it’s really one of the largest bowls that I have, and I find that it becomes something that I use for all different kinds of configurations of food and preparations of food.

It’s not just my baking bowl, it’s not a serving bowl. It’s definitely a prep bowl. But I love the heft of it, and I love how the glaze, the milky level of the glaze gives it this very soft feel on the outside. And it has over the years – the many, many years that it’s been used – it has some of those hairline cracks in the glaze that don’t compromise the bowl but almost, to me, reinforce the age and, to me, represent the history of what that bowl means. And so I, when I use it, I not only think about its utility but I also think about its history. And it’s sitting in a drawer that it’s easily accessible. I must use that bowl once a week.

Allison: Yeah, and it has a story. I bet that’s the one thing that no matter where you move, maybe not overseas, but if you need to downsize again I bet that’s a piece that you would definitely take with you and hold onto.

Anita: Oh, definitely. It’s coming with. Even if I’m overseas, it would probably come. [Laughter]

Allison: Yeah, yeah. Okay, so I have another question. I’m getting close to wrapping it up now. But I wonder, so you’ve done so much travelling to so many different parts of the world, parts of the country. What’s one thing that you haven’t tasted yet, that maybe you’ve heard of or that you’re curious about, that you would love to try and why?

Anita: Oh my goodness! What a great question.

Allison: It’s a tough one, but – [Laughter]

Anita: It is a tough one! I’m trying to think about whether it’s something that either I have missed, like there’s a seasonality to something, or a particular dish. I mean, one of the things I realized when I wrote this book is how there is an entire continent that I still need to explore, which is South America. And I am somebody that absolutely loves potatoes. It doesn’t necessarily get a lot of play in this book, but I enjoy potatoes in every sort of which way you can make them.

And I’ve been fascinated by the range and breadth of potatoes that exist in a place like Peru, where I’ve never been. I’ve always wanted to go. And there’s a part of me that would love to be able to go down there and experience – what are some of the varieties, how are those varieties presented? What, how, looking – because I enjoy potatoes in so many different ways, in so many different cultures, whether they’re julienned in Chinese dishes, mashed potatoes at Thanksgiving coming up here in North America, inside of dosa in Mumbai. I mean, potatoes are – they pop up in so many different places.

I would love to go and see, sort of returning to an origin and say, “I’d love to experience potatoes in this particular culture,” because I have in my mind almost this mythic sense of this incredible range of indigenous potatoes. And it seems to me that there would be tastes and preparations that I’ve never experienced before. And I love that ability to take what os a familiar kind of food, but to present it in a very different way. And that, that’s my experience of what would be in store for me in Peru.

Allison: Yeah, that sounds wonderful. I’m sure, now that you’ve said it out loud, I’m sure you’ll get to do it. I bet the plans will be formed within a few weeks, right? Sounds good to me.

Anita: [Laughter] Hopefully there’s some Peruvian potato association out there that’ll listen to the podcast and get in touch. I’m sure that’ll happen momentarily!

Allison: I’m sure there is, I really hope so. So-

Anita: I hope so too! [Laughter]

Allison: We’ll see, we’ll make it happen. So, I guess kind of my last question, it’s sort of open ended. But what’s your message for readers out there who might have heard this and might be ready to pick up your book or get it for someone for a gift? Or maybe even a bigger message for people who are really longing to travel and experience other cultures and other foods, but they just haven’t done it yet?

Anita: Yeah. I would hope that my book would be a little bit of a catalyst to people imagining that whatever trip that it is that they envision, that they can absolutely do it. I think that the world is there for us to explore, and there are many different ways that we can explore it. And I would hope that through the variety of examples of how I got to be in a fortunate position to have experiences in different countries, that individuals could see through this book that it’s not – that travel, travel is available in a way that it exists – the opportunities exist. And that thinking about travel as something that isn’t something that you postpone necessarily, or isn’t something that you have to wait for quote unquote “the right time.” That those opportunities can reveal themselves in different ways, and that there is so much to – there is so much that any reader that picks up my book has to offer the world. Every single one of us, there is so much that we have to offer the world. And the reciprocity in that formula is that there is so much that the world has to offer us.

And as I say in a number of the essays, for me, travelling and being a traveler is an attitude, and it’s something that you bring to your backyard and you bring to more far-flung trips. And I think that’s also my abiding message of this book, is that thinking about travel as not necessarily only associated with a passport or only associated with a form of transport, but thinking of your own two feet and your own backyard as an equally exciting and rich environment for opportunity to learn and to live as a traveler. That it’s that attitude that I have chosen to adopt for myself and that I would hope that each of us and anyone who reads my book would think about – what does it mean to walk through the world as a traveler, whether or not we’re in our own neighborhood or in a culture that’s very different from the one that we’re most familiar with and where we might live at the moment? So that, that would be my abiding wish for anyone reading the book, is to think about travel on a day to day basis.

And yes, there are these trips that we plan for and we’re excited about, and I don’t mean to minimize those at all. Those have their own allure and their own incredible experiences. But I think there is so much to be said for thinking about travel in both the regional and in a global sense. Because everyone we encounter on any given day is on a journey. They may – anyone that we encounter on any given day is travelling. And in some cases it’s a very literal travelling, like they are moving through or they are new to an environment and so that, trying to find that shared sense of empathy and that shared sense of experience and newness, I think is part of the message of my book.

Allison: Yeah. I think that’s a great message for all of our readers and our listeners to take away. So finally, where can Foodal readers go to learn more about you and about the book?

Anita: Yeah, well, I can be – you can find out more about me in a number of different locations (and I know some of these will be posted) but pepperforthebeast.com has a lot of my food writing and it has a lot of information about what makes me tick, including the Ten Things About Me, which you referenced. And then the book itself was published by Chin Music Press in Seattle, Washington. Their website is chinmusicpress.com and there’s a lot of information about the book there. […] So, those are two different places you can go. And I’m also very active on Twitter, on Facebook, on Instagram […] So, I am somebody that really believes in both the online and the offline communities that we create, so I look forward to connecting with people in either of those spaces.

Allison: Awesome, that sounds wonderful. Well, there’s so many more things that I would love to discuss with you and I really hope maybe we’ll be able to chat more in the future, maybe even share a meal together someday, who knows. But thank you so much for talking with me today, Anita. It’s been a pleasure.

Anita: Oh, Allison, thank you so much. I look forward to that meal.

Sharing Meals and Exploring the World Through Food

Did you like what you heard? Please subscribe on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts, and leave us a review. We’ll be back in about a month with the next episode!

What would you like the Foodal Podcast to explore? We want to hear from you – let us know in the comments!

Photos of slides, book cover, and recipe box by Josh Samson. Uncredited photos by Anita Crofts.

About Allison Sidhu

Allison M. Sidhu is a culinary enthusiast from southeastern Pennsylvania who has returned to Philly after a seven-year sojourn to sunny LA. She loves exploring the local restaurant and bar scene with her best buds. She holds a BA in English literature from Swarthmore College and an MA in gastronomy from Boston University. When she’s not in the kitchen whipping up something tasty (or listening to the latest food podcasts while she does the dishes!) you’ll probably find Allison tapping away at her keyboard, chilling in the garden, curled up with a good book (or ready to dominate with controller in hand in front of the latest video game) on the couch, or devouring a dollar dog and crab fries at the Phillies game.